|

Glob Reg Health Technol Assess 2022; 9: 31-35 ISSN 2283-5733 | DOI: 10.33393/grhta.2022.2350 POINT OF VIEW |

|

How reliable are ICER’s results published in current pharmacoeconomic literature? The controversial issue of price confidentiality

ABSTRACT

Pharmacoeconomic data are widely used along drug life cycle for supporting decision-making processes on research and development, pricing and reimbursement, and market access. In this context, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) is the gold standard of either cost-effectiveness analyses (CEAs) or cost-utility analyses (CUAs) of pharmaceuticals and health technologies. However, the widespread use of confidentiality clauses in the agreements between pharmaceutical companies and the payers may affect the reliability of ICER value based on transparent price. The aim of this article is to evaluate a case study and simulate the impact of price confidentiality and other managed-entry agreement conditions on the ICER value.

The case study was conducted selecting a CEA submitted to the Health Economic Evaluations Office of the Italian Medicines Agency by the pharmaceutical company, which specifically compared two alternative options reimbursed by the Italian NHS using confidential managed-entry agreements. So, a real model was used to collect the output of ICERs generated by the simulation model, considering price inputs of alternative options ranging from the transparent prices to the confidential net price.

The simulation showed that price confidentiality may affect the estimated value of the ICER of a new medicine and, consequently, its interpretation. From a different point of view, the published ICER values may also give a completely false economic evidence if non-disclosure agreements are not taken into account. A proposal for editors of pharmacoeconomic journals to improve reliability of CEA is also discussed.

Keywords: Cost-effectiveness, Cost-utility, Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, Managed-entry agreements, Price confidentiality

Received: October 19, 2021

Accepted: January 26, 2022

Published online: February 25, 2022

Global & Regional Health Technology Assessment - ISSN 2283-5733 - www.aboutscience.eu/grhta

© 2022 The Authors. This article is published by AboutScience and licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0).

Commercial use is not permitted and is subject to Publisher’s permissions. Full information is available at www.aboutscience.eu

Background

Pharmacoeconomic data are widely used along drug life cycle for supporting decision-making processes on research and development, pricing and reimbursement, and market access (1). However, these data are not only relevant for developed countries, but they are also used by the World Health Organization (WHO) in Choosing Interventions that are Cost-Effective (WHO-CHOICE) to prioritize the right settings and propose to low- and middle-income countries the proper way toward the best use of resources (2).

Recently, the burning issue of price transparency of pharmaceutical products gained the attention of the World Health Assembly (WHA), which approved a resolution in 2019 (3). Worldwide, institutional payers frequently negotiate with pharmaceutical companies non-disclosure agreements for patented medicines that are based on a variety of forms: supply contracts, risk-sharing protocols, patient access schemes, managed-entry agreements (MEAs), product listing agreements, etc. (4). A conflicting debate on this issue is currently underway, especially when a nutshell price confidentiality is considered as a source of discrimination across countries (5), and a potential failure of the market regulation due to the lack of competition (6). Specifically, in the European context, this scenario is found to be further complicated by the presence of relevant legal constraints, which prevent the sharing of information on actual prices and other conditions in non-disclosure agreements between countries (7).

However, should we assume that the implications of the confidentiality of medicine prices on market competition are the only problem? Since the treatment cost of a new pharmaceutical is a relevant component of the numerator of incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), there is no doubt that price confidentiality can also affect the main finding of cost-effectiveness analyses (CEAs) or cost-utility analyses (CUAs).

Over 40 years ago, Weinstein and Stason introduced the foundation of CEA by defining the ICER, which became the gold standard of economic evaluation of healthcare technologies (8). ICER expresses the incremental cost that should be borne for the introduction of a new intervention (e.g. a new medicine), to gain one additional unit of benefit (e.g. a quality-adjusted life year [QALY] gained, or a year of life saved), in comparison to a reference treatment (i.e. the standard of care). This ratio is used in several ways depending on the country-specific regulatory framework (9). Regardless of the actual influence of the ICERs on decision-making processes, this index is considered a measure of the overall value of new pharmaceutical products from a societal or health care system perspective (10).

Now, considering the widespread use of confidentiality clauses in the agreements for in-patent products between pharmaceutical companies and the payers (7), the pharmacoeconomic literature and/or institutional public reports can only take transparent prices into account. Indeed, confidentiality can affect the estimate of the numerator of the ICER in two ways: overestimating the cost of the new intervention; and overestimating the cost of the alternative option (whether the latter option is also subject to a confidentiality agreement). As a consequence, cost differences with available alternatives may be overestimated or underestimated, depending on the economic impact of the confidentiality agreement. Other than simple price discounts, the implementation of financial- or outcome-based agreements should also be considered. Although they do not affect purchase prices, their effects on the actual price paied by the NHS must be estimated since they may reduce the cost of the new intervention (11).

This leads to the conclusion that the ICER values published in the current pharmacoeconomic literature might be subject to criticism, since they cannot display the actual trade-off in the decision between the alternative options. In particular, the ICER value of an intervention is not real if a non-disclosure agreement is in place, and its truthfulness is progressively lower the higher the difference between the transparent price and those actually paid. Furthermore, the published ICER value can also be not reliable when the comparator is also covered by a confidentiality clause.

For these reasons, the Italian Medicines Agency started to publish institutional health technology assessment (HTA) reports of innovative pharmaceutical products using the actual net prices for both intervention and comparator, resulting after price negotiation (i.e. prices reduced by all rebates, discounts, and other terms negotiated and agreed with pharmaceutical companies) (6). The publication of CEA results does not infringe the legal clauses in the confidential agreements (12), since. This was done by hiding the cost per patient and the total costs generated by intervention and comparator and reporting only the actual incremental cost and the corresponding ICER value.

ICER at final net prices and confidentiality

The aim of this section is to evaluate a case study and simulate the impact of price confidentiality and other MEA conditions on the ICER value. The Health Economic Evaluations Office of the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA) receives from the pharmaceutical companies the simulation models used for performing CEAs or CUAs of their own products. These models are part of the price and reimbursement dossier submitted for a full technology assessment (13,14). Furthermore, the AIFA’s office also knows both the official transparent price that is published in the Italian official journal, and the net negotiated price in charge to the National Health Service (NHS). So, it anonymously used a real model to collect the output of ICERs generated by the simulation model, considering price inputs of alternative options ranging from transparent prices to the confidential net prices.

Among the several simulation models submitted to AIFA by pharmaceutical companies, the case study was conducted selecting a cost-effectiveness analysis which specifically compared two alternative options reimbursed by the Italian NHS using confidential MEAs. So, the case study considered the impact of confidentiality on the ICER of the new product, and also the interaction between price confidentiality of the same product with that of the reference treatment.

In order to ensure the complete anonymization of the case study, both the outputs of the simulation model and the confidential price discounts were changed by a random factor.

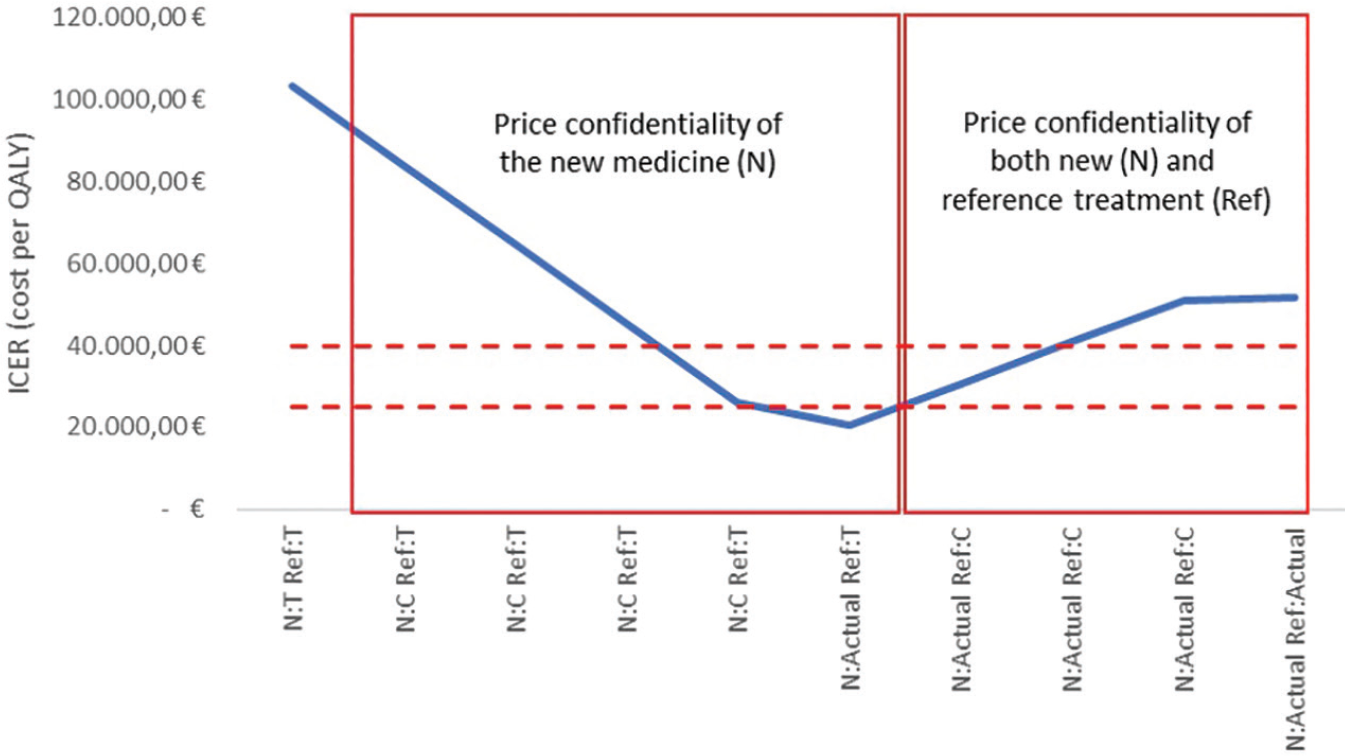

Figure 1 shows the ICER outputs of the case study. The ICER value calculated using transparent prices for both alternative options is over 100,000 euros per QALY, largely higher than a reasonable threshold range of a cost-effective treatment for the Italian context (dotted lines), according to the guideline of the Italian Health Economics Association (AIES; 15). Although it is the only one that can be published in pharmacoeconomic literature without infringing any confidential contractual arrangements, this value of ICER is unrealistic due to the price confidentiality implemented. Actually, by increasing the value of the confidential price discount until the final net price is reached, the ICER value of the new medicine went even under the threshold range for cost-effective treatments according to the recommendation provided by AIES (15).

Fig 1 - ICER outputs from the pharmacoeconomic model of the case study according to the presence/absence of price confidentiality and other managed-entry agreement conditions, for the new medicine (N) and/or the reference treatment (Ref).

The graph shows the ICER outputs from the pharmacoeconomic model based on different price inputs for both the new and the reference treatment. Box on the left: the ICER outputs were obtained by increasing the confidential discount of the new medicine (C - or other MEA conditions) up to its actual negotiated value, in relationship with the transparent price (T) of comparator. Box on the right: the ICER outputs were obtained by increasing the confidential discount of the reference treatment up to its negotiated value, in relationship with the actual price of the new medicine.

Despite the new medicine now being a cost-effective option for the Italian context, this scenario is not reliable since it does not consider the net price of the reference treatment. When an increasing confidential discount for the reference treatment (until the final net price is reached) was used to inform the simulation model, the ICER of the new medicine was over the threshold range for cost-effective treatments according to AIES recommendations (15).

Hence, the current case study showed that price confidentiality seems to have a non-negligible effect on the estimated value of the ICER and, consequently, on its interpretation. From a different point of view, the published ICER values may give a completely false economic evidence if non-disclosure agreements are not taken into account.

However, it could be argued that the publication of an ICER based on net prices could lead to an infringement of the confidentiality clause of MEAs. This condition would be true if 100% of the total cost of the new option is represented by the acquisition cost of the new medicine alone, and simultaneously, a confidential price was not adopted for the reference treatment. Nevertheless, this is an implausible scenario, as the reason for performing a CEA is exactly to estimate the economic impact in terms of both savings and burdens on other healthcare and non-healthcare costs in addition to the acquisition cost of the drug.

In other terms, the acquisition cost of the new medicine is always a portion of the total cost of the new option in CEA and this portion can variably change depending on the percentage of confidential discount and the effect of other MEAs. Consequently, compared with the scenario of transparent prices, the percentage variation of the ICER calculated with net prices is always different from the percentage variation due to the acquisition net price.

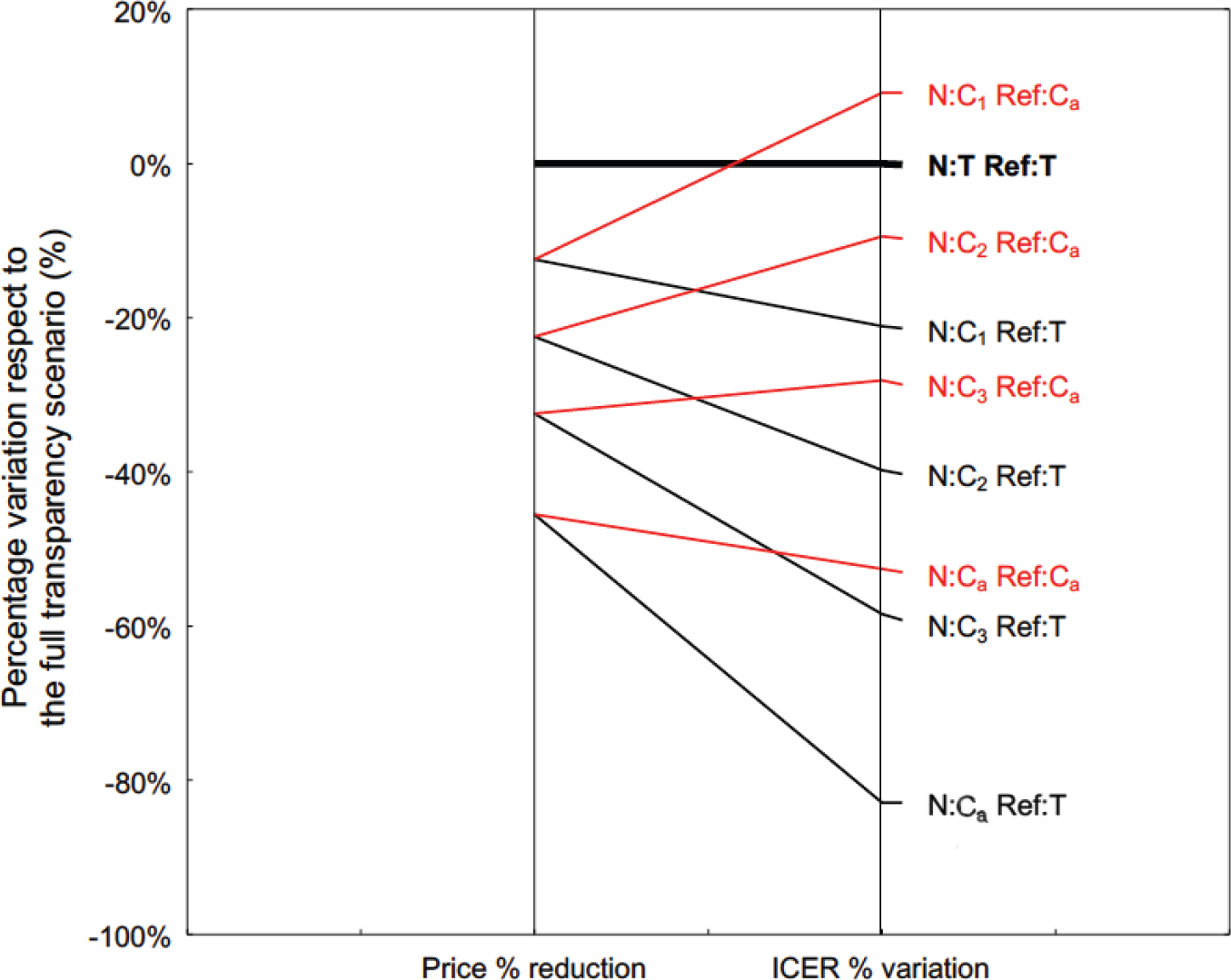

Figure 2 shows the simulation result of this hypothesis. The simulation was conducted from the perspective of the public payer at the end of price negotiation of a new medicine (N) with the pharmaceutical company. If the percentage of reduction of confidential price after negotiation compared with the transparent one corresponds to the percentage variation included in the resulting ICERs, the publication of an ICER obtained using the confidential net price infringes the non-disclosure agreement. Thus, the simulation considers several ICER model outputs obtained when the price input corresponds to the transparent prices published in the Italian Official Journal (T), or the range of decreasing confidential prices (from C1 to C3) until the actual net price resulting from the application of non-disclosure agreements (Ca). The simulation was conducted setting the reference price of the treatment (Ref) at both T and Ca values.

With respect to the condition that would confirm the hypothesis given by the horizontal line of a full transparency scenario (i.e. transparent prices T for both the new medicine and the reference treatment), the same pattern does not occur in any of the other alternative scenarios using confidential prices. As expected, the percentage variation of ICERs is always different from the percentage reduction of the acquisition price, and the slope of the line depends on the incidence of the acquisition cost of N on the total cost of CEA. Overall, the presence of a confidential price also for Ref increases the ICER of N (i.e. a transparent price for Ref gives an optimistic ICER value of N).

Fig 2 - Percentage price reduction of the new medicine (N) with respect to its transparent one (left side), and the corresponding percentage variation of the ICER model output (right side). The full transparency scenario (bold black line) considers transparent prices for both N and reference treatment (Ref). The lines reflect the alternative scenarios under non-disclosure agreement: the ICER model output was obtained after setting the confidential price of N at decreasing levels (C1, …, C3), until the actual net price reimbursed by the NHS (Ca). The Ref price in the model was set at both the transparent price (black lines) and the actual net price (red lines). ICER = incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; NHS = National Health Service.

Although the pharmacoeconomic model is real, the percentage differences shown in Fig. 2 have been increased by a random factor to ensure further protection of the confidentiality agreement.

In conclusion, the publication of CEAs including ICERs based on confidential prices does not infringe the confidential clause of the MEAs and provides a true and reliable estimate of the cost-effectiveness of a new treatment from the payer’s perspective.

Proposal to editors of pharmacoeconomic journals

The main aim of pharmacoeconomic modelling is to structure the evidence available at the time of authorization about clinical and economic outcomes that may be used to inform pricing and reimbursement decisions, and efficient healthcare resource allocation (16). The assessment of model quality fell into three areas: model structure, data used as inputs to inform models, and model validation (17). In particular, the current article focused on the second area, since medicine prices of alternative options are relevant input data for pharmacoeconomic models.

In order to increase transparency and reliability of CEA/CUA results in pharmacoeconomic literature, a proposal for editors will be presented in this section. The proposal can be applied to CEA/CUA for new medicinal products: (i) before the price negotiation of a new medicine by the national competent authorities, when compared to a reference treatment whose price is established as part of a confidential MEA; (ii) after the price negotiation of a new medicine covered by a non-disclosure agreement, whether or not it is compared with a reference treatment whose price is set in the context of a confidential MEA.

In the case of publication of CEA or CUA, editors of pharmacoeconomic journals should consider the adoption of devoted rules necessary to manage the confidentiality clause in the MEA.

The manuscript of an economic analysis is confidential if the editor does not authorize its publication, and the sharing of the manuscript with experts appointed by the journal to conduct a peer review is also confidential.

Therefore, the proposal is that Authors can obtain from pharmaceutical companies the net price by signing a non-disclosure agreement. Subsequently, the authors develop the CEA/CUA according to the quality standards set by the journal. The experts who carry out a peer-review process can check the methodology used by the authors and the results usually reported. However, the authors have to produce the table showing unit costs for CEA/CUA in a double format: one for reviewers reporting net drug prices and a second identical one including transparent prices instead.

At the end of the peer reviewing, the editor of the journal will authorize the publication obscuring both the unit costs based on actual prices and the total actual costs of the alternatives under comparison (Tab. I).

| Expected values | Reference treatment [Ref] | New medicine [N] | Incremental difference

[Δ=N-Ref] |

ICER |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cost | €94,940.59 | €369,078.52 | € 200,000.00 | – |

| Life years | 2 | 10 | 8 | € 25,000 |

| QALYs | 1.5 | 8 | 6.5 | € 30,769 |

The table reports fancy numbers, and it does not reflect the output from the case study model.

CEA = cost-effectiveness analysis; CUA = cost-utility analysis; ICER = incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; MEA = managed-entry agreement; QALY = quality-adjusted life year.

In the Italian context, alternatively the final prices obtained after public tenders could be used. Though these prices are net of confidential discounts, they do not consider any economic effect of other forms of financial agreement of a MEA such as rebates, paybacks, credit notes, etc. Furthermore, a recent survey evidenced that in Europe, despite the European Transparency Directive, in 77% (17 out of 22) of respondent countries the final price reached after public tenders is not published (7).

Finally, as proposed, the adoption by editors of pharmacoeconomic journals of a specific format useful to promote the utilization of net prices in CEA/CUA could be valuable to increase both the transparency without infringement of the confidentiality clauses of MEAs and the reliability of ICER values in the pharmacoeconomic literature.

Acknowledgements

Opinions reported in this article are personal and do not necessarily represent the position of the Italian Medicines Agency or of one of its committees or working parties.

Disclosures

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1. Langley PC. Focusing pharmacoeconomic activities: reimbursement or the drug life cycle? Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20(2):181-188. CrossRef PubMed

- 2. Bertram M, Lauer J, Stenberg K, Edejer T. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care interventions for priority setting in the health system: an update from WHO CHOICE. IJHPM; 2021. Available at: CrossRef. Accessed July 5, 2021.

- 3. World Health Organization. Resolution WHA72.8: Improving the transparency of markets for medicines, vaccines, and other health products. Geneva: World Health Assembly 72; 2019. Available at: Online. Accessed July 5, 2021.

- 4. Morgan SG, Vogler S, Wagner AK. Payers’ experiences with confidential pharmaceutical price discounts: A survey of public and statutory health systems in North America, Europe, and Australasia. Health Policy. 2017;121(4):354-362. CrossRef PubMed

- 5. Morgan SG, Bathula HS, Moon S. Pricing of pharmaceuticals is becoming a major challenge for health systems. BMJ. 2020;368:14627. CrossRef PubMed

- 6. Rintoul A, Colbert A, Garner S, et al. Medicines with one seller and many buyers: strategies to increase the power of the payer. BMJ. 2020;369:m1705. CrossRef PubMed

- 7. Russo P, Carletto A, Németh G, Habl C. Medicine price transparency and confidential managed-entry agreements in Europe: findings from the EURIPID survey. Health Policy. 2021;125(9):1140-1145. CrossRef PubMed

- 8. Weinstein MC, Stason WB. Foundations of cost-effectiveness analysis for health and medical practices. N Engl J Med. 1977;296(13):716-721. CrossRef PubMed

- 9. Jommi C, Armeni P, Costa F, Bertolani A, Otto M. Implementation of value-based pricing for medicines. Clin Ther. 2020;42(1):15-24. CrossRef PubMed

- 10. Lakdawalla DN, Doshi JA, Garrison LP Jr, Phelps CE, Basu A, Danzon PM. Defining elements of value in health care – a health economics approach: an ISPOR Special Task Force report [3]. Value Health. 2018;21(2):131-139. CrossRef PubMed

- 11. Russo P, Marcellusi A, Zanuzzi M, et al. Drug prices and value of oncology drugs in Italy. Value Health. 2021;24(9):1273-1278. CrossRef PubMed

- 12. Italian Medicines Agency. Technical-scientific reports. Available at: Online. Accessed July 5, 2021.

- 13. Italian Medicines Agency. Economic evaluations. Available at: Online. Accessed July 5, 2021.

- 14. Carletto A, Zanuzzi M, Sammarco A, Russo P. Quality of health economic evaluations submitted to the Italian Medicines Agency: current state and future actions. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2020;36(6):560-568. CrossRef PubMed

- 15. Fattore G. Proposta di linee guida per la valutazione economica degli interventi sanitari in Italia. PharmacoEcon Ital Res Artic. 2009;11(2):83-93. CrossRef

- 16. Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

- 17. Weinstein MC, O’Brien B, Hornberger J, et al; ISPOR Task Force on Good Research Practices – Modeling Studies. Principles of good practice for decision analytic modeling in health-care evaluation: report of the ISPOR Task Force on Good Research Practices—Modeling Studies. Value Health. 2003;6(1):9-17. CrossRef PubMed