|

Glob Reg Health Technol Assess 2020; 7(1): 117-123 DOI: 10.33393/grhta.2020.2143 ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE |

|

Towards standardization of economic evaluation research in the youth psychosocial care sector: A broad consultation in the Netherlands

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Stakeholders are increasingly interested in the societal impact of psychosocial interventions in the youth sector, in terms of costs and quality of life, as well as in outcomes research. The aim of this broad consultation was to reach consensus regarding the steps to be undertaken to set a research agenda for the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) programme.

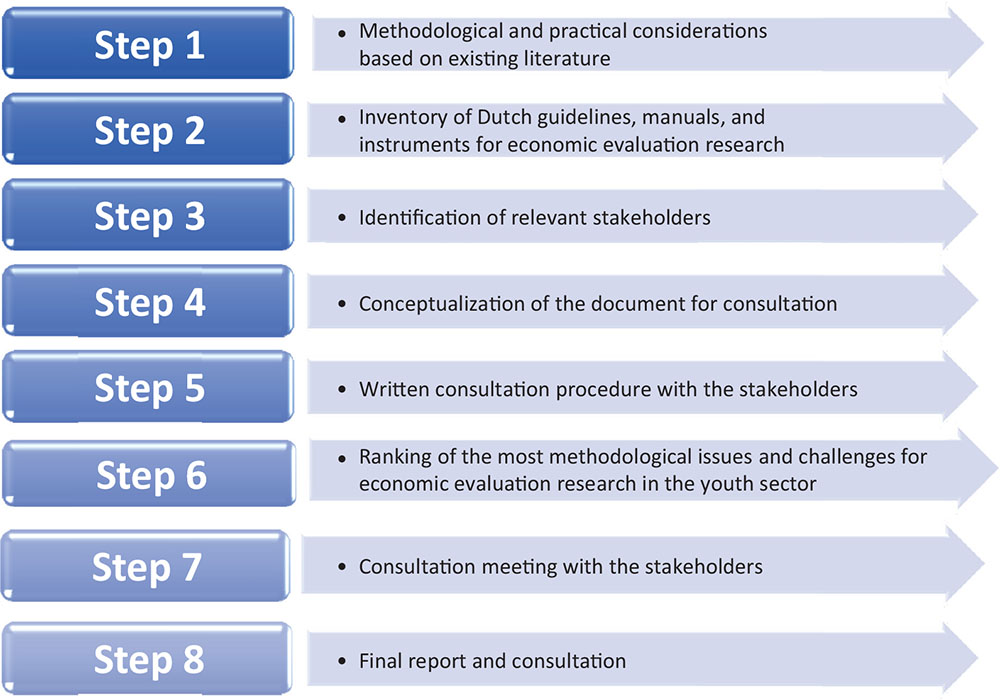

Methods: The broad consultation consisted of an eight-step procedure, including the conceptualization of a consultation document consisting of a scoping review of (mainly) international opinion/methodological literature and an inventory of existing Dutch guidelines and manuals for economic evaluation, a written consultation procedure among a broad range of stakeholders, and a consultation meeting with these stakeholders.

Results: In total 21 documents were included in the scoping review. A total of 24 stakeholders participated in the written consultation procedure and 14 stakeholders during the consultation meeting. The methodological issues and challenges, which were ranked in the top 5 by the stakeholders, are (i) outcome measurement, (ii) outcome identification, (iii) cost valuation, (iv) outcome valuation, and (v) time horizon/analytical approach. The existing guidelines and manuals provided guidance for some, but not all, issues and challenges.

Discussion and Conclusion: This broad consultation has contributed to a research agenda for the ZonMw programme, which will in the long run lead to the standardization of economic evaluations in this sector in the Netherlands and methodological improvement of economic evaluations in the Dutch youth sector.

Keywords: Adolescence, Adolescent psychiatry, Cost-benefit analysis, Expert opinions, Quality of life, Review

Received: July 16, 2020

Accepted: October 28, 2020

Published online: December 14, 2020

© 2020 The Authors. This article is published by AboutScience and licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0). Any commercial use is not permitted and is subject to Publisher’s permissions. Full information is available at www.aboutscience.eu

Introduction

Stakeholders are increasingly interested in the societal impact of psychosocial interventions in the youth sector, in terms of costs and quality of life (QoL), as well as in outcomes research. As a result, increasing attention is being focused on economic evaluation studies in the youth sector. Not only is there an increasing interest in economic evaluations in the youth sector, but these economic evaluations are increasingly being conducted from a societal perspective (1,2). This means that these economic evaluations are performed from a broad perspective, in which the analyst considers all costs and effects that flow from the intervention, regardless of who experiences these (3).

However, methods and instruments which are used in economic evaluations have mainly been developed for somatic (health) care and moreover for an adult population using (a more narrow) health care perspective, making it challenging to perform economic evaluations in the youth sector. The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) programme, working effectively in the youth sector, initiated a consultation to set a research agenda, which will contribute to further methodological development of health economic methods in the youth sector and the standardization of economic evaluations in this sector in the Netherlands. The definition of the youth sector, in line with this research programme, in this consultation encompassed psychosocial care for children and youngsters, more specifically following (current) Dutch sectors: mental health care in youth, local preventive youth care policy, and/or clients on the cutting edge between indicated youth care/mental health in youth/youths with a mild intellectual disability. This implies that issues and considerations specifically related to economic evaluations of somatic care in youth, such as hospital care, were not the focus of this broad consultation. The term ‘youth’ is used for both children and adolescents. The aim of this broad consultation was to reach consensus regarding the steps to be undertaken to set a research agenda for the ZonMw programme, which will contribute to further methodological development of health economic methods in the youth sector and the standardization of economic evaluations in this sector in the Netherlands.

Methods

In order to reach this aim, an eight-step approach has been undertaken (see Fig. 1). This eight-step approach was chosen as it allows an interactive triangulation between scientific literature, health economics guidelines, and the experience of health economists and other stakeholders in psychosocial youth care. The approach has been consolidated in a research proposal, which has been reviewed and approved by the ZonMw programme working effectively in the youth sector. This ZonMw programme is organized into six consortia aiming at the condensation of interventions regarding youth on six themes, namely: (i) social skills/insecurity/resilience; (ii) anxiety, depression, dysthymic problems, and other internalizing behavioural problems; (iii) boisterous behaviour and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD); (iv) externalizing behavioural problems/disorders; (v) parenting uncertainty – prevention and mild problems; (vi) severe problems with parenting/multiproblem families.

First, a rapid/scoping review was performed regarding methodological issues and (practical) challenges for economic evaluation research in the youth sector. A scoping review focuses on a much broader field, in comparison to a systematic review, and maps the key concepts, theories, sources, and knowledge gaps within a certain (research) area (4). In our case, the scoping review aims at providing an inventory of potential problem areas for which (further) standardization or further research is needed for economic evaluations in Youth Psychosocial Care Sector in the Netherlands. Apart from published literature, conference proceedings, abstracts, and relevant presentations were included. The review focused mainly on opinion, methodological and tutorial-like papers and did not include empirical studies (i.e. economic evaluations performed in the field of youth research). Search terms for retrieving potentially relevant papers were: challenges, issues, methods/methodological, considerations, problems AND youth, children, infants, youngsters, paediatric AND costs, cost-effectiveness, economic evaluation, QoL, Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALY). Furthermore, references of the identified papers were checked for additional papers. The issues that were retrieved from the literature search were complemented with suggestions provided by members of the consortia during an earlier meeting. Methodological issues and (practical) challenges were categorized by the framing aspects of an economic evaluation (perspective, time horizon, analytical approach, outcomes, costs, type of economic evaluation, and target population). The framing aspects outcomes and costs were further categorized into: identification, measurement, and valuation. The issues and considerations that were retrieved from the literature were not judged for their relevance; we merely collected, classified, and tabulated them.

Second, an inventory and substantive study was performed looking at existing Dutch guidelines, manuals, and instruments (such as resource use measurement instruments, utility questionnaires in Dutch) for economic evaluation research. For this step, an internet search was combined with the consultation of the health economic expert in the Netherlands. The aim of this inventory was to reveal – if any and if so – which methodological issues and challenges, identified in the first step, were already addressed in the existing Dutch guidelines, manuals, and instruments for economic evaluation research.

Third, a written consultation among Dutch stakeholders was held. For this purpose, a consultation document was conceptualized, which (i) gave a systematic overview of the methodological issues identified and (practical) challenges for economic evaluation research in the youth sector and (ii) if and how these issues are addressed in existing Dutch guidelines, manuals, and instruments for economic evaluation research. The consultation document was sent to the so-called ‘performing stakeholders’, consisting of researchers who carry out economic evaluation research in the youth sector. We included health economic evaluation experts, members of consortia on Youth research, Dutch knowledge institutes, the National Health Care Institute (ZiNL), and organizations for professionals in the field of health technology assessment/economic evaluation research, such as the Dutch/Flemish Organisation of Health Economics (VGE) and the Dutch Society for Health Technology Assessment (NVTAG).

In the written consultation, the stakeholders were individually asked to give an overall impression of the consultation document by means of a survey. In this survey we asked them to suggest additional methodological issues and (practical) challenges for economic evaluation research in the youth sector; suggest additional existing Dutch guidelines and manuals for economic evaluation research, suggest additional literature, which is relevant for the scoping review (for Step 1); prioritize methodological issues and (practical) challenges for economic evaluation research in the youth sector in order of importance (rank a maximum of the 10 most important methodological issues and challenges, including any additional ones suggested by the stakeholder themselves); suggest possible (procedural) solutions for the methodological issues and challenges which are included in the top 10 – these suggestions might include adapting the existing guidelines (including adding module(s) to the existing guidelines), adapting existing sets of instruments, suggestions for additional research, etc. Stakeholders were asked for consent to expose their names.

Fourth, the most relevant methodological issues and challenges for economic evaluation research in the youth sector were identified based on the rankings of the stakeholders. Issues that were ranked most important were assigned 10 points; least important issues were assigned 1 point. If, for example, only three issues were ranked, a maximum of 3 points was assigned to the most important issue. The issues were subsequently clustered into the framing aspects. Furthermore, based on feedback from the respondents, the consultation document was then adapted accordingly.

Fifth, the adapted consultation document was discussed in a final consultation meeting. The purpose of this meeting was to further prioritize the steps to be taken in order to come to a standardization of economic evaluation research for the youth sector. Next to the ‘performing’ stakeholders, also ‘using’ stakeholders were invited to this consultation meeting. The ‘using’ stakeholders are those who will use the results of economic evaluation research for (research) policy and practice, for example, at a national, municipal, or institutional level. They are the ones who can stipulate the conditions and the methods of economic evaluation research in the field of youth research and consisted of umbrella organizations for practice; umbrella organizations for schools and education; umbrella organizations for the municipalities and provinces; the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport; the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science; the Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment; and the Ministry of Security and Justice. Following this consultation meeting the final report was drafted (5).

Results

Results of rapid review

For the review we included 23 publications (6-28). A detailed listing of the methodological issues and (practical) challenges for economic evaluation research in the youth sector, categorized by the framing aspects, can be found in supplementary materials (see supplementary table 1). Results are summarized below and organized according to the framing aspects.

Although most seem to agree on the perspective which, in principle, should be the broad societal perspective, the distribution of costs and effects over different stakeholders should receive more explicit attention. Furthermore, taking a societal perspective raises the challenge of identifying and measuring the broad range of resources used and outcomes, as well as the potential danger of double-counting costs and consequences.

Although it is recognized that the time horizon should be long enough to capture all downstream costs and benefits over time, most economic evaluations in the youth sector have applied a short time horizon, reasons being that stakeholders may request a swift answer, resources may be limited, there may be a limited time horizon in the call for proposals, and limited possibilities for a valid long-term follow-up due to a high nonresponse. As a consequence, there is a lack of data available which can be used as input for long-term modelling studies, and there is the danger of forecasts being unreliable. Furthermore, due to the many transitions that a youngster goes through over time, it may also be difficult to establish whether there is still a causal relationship between the original intervention and (positive) effects over time.

Regarding the measurement of resource use and the valuation of costs, it is mentioned that there is no standard available for identifying the broad range of services and types of resources that might be relevant for the analysis. Instruments for measuring resource use in youth are either lacking or based on instruments developed for adults and have not been properly validated for use in youth. Furthermore, it can be difficult and time-consuming to gain access to existing databases or registries, and self-reported measures may suffer from recall bias and raise the question whether data from youngsters themselves, proxy reports, or multiple informants should be used for analysis. Finally, it is noted that no (Dutch) standardized unit costs are available, nor is there a standardized method for calculating costs, which fall in sectors other than health care, such as social services, education/school services, and criminal justice.

With respect to outcome(s) in economic evaluation in the youth sector, it is put forward that the scope of relevant (targeted and non-targeted) outcomes may be difficult to determine, and that each stakeholder may focus on different desired outcomes. Consequently, it is unclear which type of economic evaluation should be the standard. Moreover, in a cost-utility analysis (CUA), QALY of the youngsters (based on preference-based measures like the EuroQol-5 dimensions EQ-5D) do not capture outcomes beyond health, nor do QALYs include benefits gained by other persons, for example, parents, family, or other stakeholders. This raises the question of what the appropriate unit of analysis is – should this be the youngster, their family, or broader? In a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), the focus is on one target (natural) outcome and this may be too narrow to capture all relevant (targeted and non-targeted) outcomes. In a cost-consequence analysis (CCA), the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios based on different outcomes may point to different interventions being cost-effective. In a cost-benefit analysis (CBA), both the selection and conversion of outcomes to money were considered problematic.

Much of the literature (see supplementary table 1, available as supplementary material) focused on the problems and challenges in the measurement of health and (health-related) QoL in youth. In general, there is a lack of validated (preference-based) QoL instruments specifically developed for youth, and if available, more research should be dedicated to establishing the feasibility and measurement properties of these instruments.

Adapting adult measurements for use in youth research may be questionable, as the concept and relevant dimensions of health/QoL, especially in children, are likely to differ from those in adults, and may even be age-dependent. Furthermore, children at various ages have difficulties understanding and reporting their health/QoL, due to limited cognitive abilities and linguistic skills, in comparison with adults.

Although it is generally agreed that QoL is subjective, and that a QoL instrument should reflect the perspective of the child, proxy reports of health/QoL may be necessary to replace or complement the self-reports of children. However, proxy reports of a child’s health or QoL may be confounded by the proxy’s own value system and how the proxy (or others in the family) is affected by the child’s condition. Furthermore, proxy reports may be problematic due to weak agreement between child and proxy (e.g. parent and child) or between different proxy respondents (father or mother), the latter raising the question who the appropriate proxy is. If, in addition to the QoL measurement of children, the QoL is also measured for people who are close to the child, for example, the parents, then generally this is done without consideration that there is a QoL trade-off (i.e. utility interdependence) between family members.

With respect to valuation of outcomes, there is a lack of valuation sets specifically developed for youth in order to construct utility scores. Existing valuation sets based on adults’ preferences may not be appropriate for reflecting the experiences of children and adolescents. Health state valuations performed by children themselves raise similar problems as in health/QoL measurement, due to children’s limited cognitive and linguistic abilities. In addition, children may have a different attitude towards risk or may have difficulty comprehending the concept of time, or the possibility of death. Alternatively, proxy valuations can be used. However, proxy valuations raise the same issue as mentioned earlier in regard to the health/QoL measurement, with respect to who the appropriate proxy is, weak agreement between the child’s and proxy valuations, and confounding due to the proxy’s own value system and utility interdependence, the latter also being influenced by the perspective of the proxy.

Finally, the youth population is heterogeneous with respect to age, ethnicity and cause of the problem (behaviour)/condition, which may impact the results of economic evaluations. Also, there may be problems in gaining access to youth.

Existing guidelines, manuals, and instruments

For this consultation the following guidelines, manuals and instruments for economic evaluation were studied:

- Bouwmans CAM, Schawo SJ, Jansen DEMC, Vermeulen KM, Reijneveld SA, Hakkaart-van Roijen L. Handleiding Vragenlijst Intensieve Jeugdzorg: Zorggebruik en productieverlies. Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam, 2012 (29);

- Bouwmans C, Schawo S., Hakkaart-van Roijen L. Handleiding Vragenlijst TiC-P voor kinderen. Rotterdam: iMTA, Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam, 2012 (14);

- Delwel, GO. Leidraad voor Uitkomstenonderzoek ‘ten behoeve van de beoordeling doelmatigheid intramurale geneesmiddelen’ Op 1 december 2008 vastgesteld en uitgebracht aan de Minister van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport. College voor zorgverzekeringen, 2008 (30);

- Drost R, Paulus A, Ruwaard D, Evers S. Handleiding intersectorale kosten en baten van (preventieve) interventies. Universiteit Maastricht, 2014 (31);

- Romijn G, Renes G. Algemene leidraad voor maatschappelijke kosten-batenanalyse. Den Haag: Centraal Planbureau/Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving, 2013 (32);

- Pomp M, Schoemaker CG, Polder JJ. Themarapport Volksgezondheid Toekomst Verkenning (VTV). Op weg naar maatschappelijke kosten-baten analyses voor preventie en zorg. Bilthoven: Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu, 2014 (33);

- EQ-5D-Y instrument (Dutch version). www.euroqol.org (34,35);

- Zorginstituut Nederland. Kostenhandleiding: Methodologie van kostenonderzoek en referentieprijzen voor economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg. Zorginstituut Nederland, 2015 (36);

- Zorginstituut Nederland. Richtlijn voor het uitvoeren van economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg. Zorginstituut Nederland, 2015 (37).

Overall, very few methodological problems are solved in the existing Dutch guidelines and manuals, especially if we focus on the target population of this consultation, that is, youngsters. Some of the guidance documents touch upon some similar issues as in the scoping review, albeit mostly without providing any concrete solutions or alternatives.

Written and final consultation

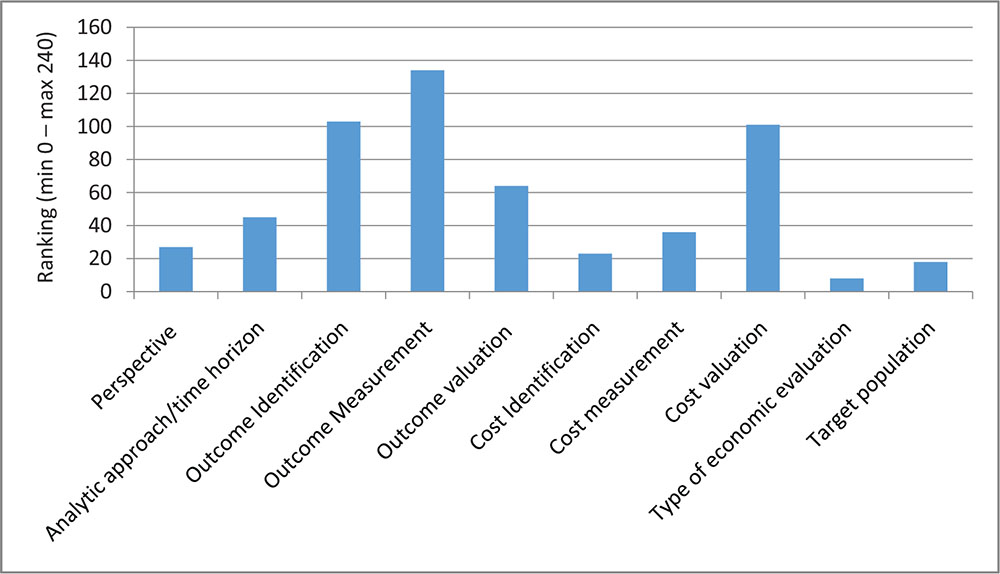

The consultation document was sent out to 34 ‘performing’ stakeholders, including the two organizations for professionals in the field of health technology assessment/economic evaluation research. In addition, the document was sent to the six consortia. Consortia leaders were asked to forward the consultation document to the consortia members and ‘using’ stakeholders. Nineteen feedback forms were received from 24 stakeholders. Respondents consisted of 13 researchers in the field of health economics/health technology assessment, 5 knowledge institutes, and the Dutch/Flemish Health Economics Association. Results of the ranking procedure are presented in Figure 2. In case all 24 respondents would have placed a topic as the most important in their top 10, this topic would have received the value 240 in Figure 2.

In order of importance, the topics were: outcome measurement, outcome identification, cost valuation, outcome valuation, time horizon/analytical approach, cost measurement, perspective, cost identification, target group, and type of economic evaluation. Remarkably, outcome identification, outcome measurement, and outcome valuation all ranked in the top five. This confirms the findings of the review, in which many issues and considerations related to these topics were put forward. Cost valuation and time horizon/analytical approach were also among the five most important topics.

A few suggestions for other methodological papers and instruments were made. Some additional issues were also put forward. One was directed at the possibility of transferring economic evaluations from other jurisdictions to the Netherlands. It was also noted that attention should be paid to design issues, as a randomized design is not always attainable in the youth sector (25). In case of alternative designs, like observational studies, one should be aware of potential biases. In relation to this, the potential use and validity of ‘routine outcome measurements’ (ROM), databases, and registries for economic evaluations were put forward. Some issues were not directly related to economic evaluation, but to the choice of working mechanisms and moderators of interventions and programmes under evaluation.

Discussion

The objective of the broad consultation procedure was to reach consensus regarding the steps to be undertaken towards further methodological development and the standardization of economic evaluations in the youth sector. In order to reach this objective a systematic approach was chosen, which included a scoping review of the international opinion/methodological literature and an inventory of existing Dutch guidelines/manuals for economic evaluation. On two occasions, stakeholders had the possibility to provide their input, that is, in the written consultation 24 stakeholders gave their input and 14 stakeholders participated in the consultation meeting.

This broad consultation resulted in a clear ranking of the methodological issues which were regarded as being most important for the further development of economic evaluation in the youth sector. The issues ranked in the top 5 by the stakeholders are: (i) outcome measurement, (ii) outcome identification, (iii) cost valuation, (iv) outcome valuation, and (v) time horizon/analytical approach. Existing Dutch guidelines and manuals provide guidance for some, but not all, issues and challenges. For the outcome side of the economic evaluation, normative questions have been posed such as: What is the goal of psychosocial care for youth that the outcome(s) in economic evaluations should comply with, and whose values count when obtaining preference weights for the outcome? Furthermore, respondents urged that they are in need of instruments specifically developed for youth to perform economic evaluations, such as instruments for measuring costs, preference-based instruments for measuring QoL (utilities), and cost prices (e.g. for interventions, education, social care, and police/justice). With respect to other methodological challenges, stakeholders generally agreed that the overall guidelines should be applied to the youth sector.

To our current knowledge this is (inter)nationally the first broad consultation identifying methodological challenges and providing the groundwork for the standardization of economic evaluations in the youth sector. This broad consultation has several strengths. First, we included a large group of (academic) experts from different backgrounds. Second, this consultation was based on a systematic approach, in which the authors were transparent about each step undertaken. Third, during the scoping review and the consultation, we deliberately took a non-normative approach, meaning that all issues were included during the scoping review and during the consultation, without judging or selecting the issues according to their relevance.

Although overall the stakeholders considered the consultation document to be complete, transparent, detailed, consistent, useful, and interesting, some limitations of this work were also put forward and need to be considered. First, during the inventory of existing guidelines/manuals for economic evaluation, we included materials only from the Netherlands, as this consultation focuses on the Dutch situation. As was mentioned during the written consultation, a systematic analysis of the international guidelines for economic evaluation might reveal additional ideas and solutions, which are not reflected in the Dutch documents. In relation to this, consulting the broader international literature, outside the scope of economic evaluations, was recommended, for potential guidance and ‘best practices’ with respect to some methodological issues, such as proxy measurement. Second, although we included a large diversity of experts, not all relevant stakeholders were present during the broad consultation. For example, we did not include children and their parents as stakeholders in the broad consultation. In addition, during this consultation we received input mainly from the first group of stakeholders – the ‘performing’ stakeholders (academic researchers, members of the six consortia, and knowledge institutes), while the ‘using’ stakeholders (umbrella organizations from practice, school, and the government) did not attend the broad consultation. Third, although the aim of the broad consultation was to reach consensus regarding steps to take towards the standardization of economic evaluations in the youth sector, there was no time to complete a full consensus procedure, which should be done, for example, by means of several Delphi rounds. In this broad consultation, we completed only one round (exploration of issues and ranking in the written consultation procedure and discussion in the stakeholders meeting). Nevertheless, we obtained a clear prioritization of issues, which serves as guidance for further actions. Based on this, further research is commissioned by the ZonMw leading to an overview of QoL and cost questionnaires in children (38) and a database of instruments and factsheets on economic evaluation at the Netherlands Youth Institute (39).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the stakeholders for their valuable input and feedback, both during the written consultation as well as during the stakeholder consultation meeting. Additionally, several colleagues gave much-appreciated input during consultation meetings. A special word of thanks to the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) programme ‘Effectief werken in de jeugdsector’ for commissioning this consultation and to the members of the six consortia, which have been established under this programme.

Disclosures

Conflict of interest: Authors disclose no conflict of interest.

Financial support: Financial support for this study was granted by the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) programme ‘Effectief werken in de jeugdsector’.

References

- 1. Drost RMWA, Paulus ATG, Evers SMAA. Five pillars for societal perspective. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2020;36(2):72-74.

- 2. Drost RMWA, van der Putten IM, Ruwaard D, Evers SMAA, Paulus ATG. Conceptualizations of the societal perspective within economic evaluations: a systematic review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2017;33(2):251-260.

- 3. Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, Weinstein MC. Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. New York: Oxford University Press 1996.

- 4. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467-473.

- 5. Dirksen CD, Evers SMAA. Broad consultation as part of the standardization of economic evaluation research in the youth sector. Maastricht: Maastricht University 2016.

- 6. Coghill D, Danckaerts M, Sonuga-Barke E, Sergeant J; ADHD European Guidelines Group. Practitioner review: quality of life in child mental health - conceptual challenges and practical choices. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50(5):544-561.

- 7. Dirksen CD, Evers SMAA, Joore M. Notitie Economisch evaluatieonderzoek binnen het programma jeugd. Maastricht: academisch ziekenhuis Maastricht/Universiteit Maastricht 2007.

- 8. Dirksen CD. Kosteneffectiviteit van jeugdzorg. ZonMW, 21 April 2015.

- 9. Drost RM, Paulus AT, Ruwaard D, Evers SM. Inter-sectoral costs and benefits of mental health prevention: towards a new classification scheme. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2013;16(4):179-186.

- 10. Drotar D. Validating measures of pediatric health status, functional status, and health-related quality of life: key methodological challenges and strategies. Ambul Pediatr. 2004;4(4):358-364.

- 11. Evers S. Kosteneffectiviteit voor interventies in de jeugdgezondheidszorg: resultaten en methodologische uitdagingen. Rotterdam: National Congres Volksgezondheid 2015.

- 12. Frick KD, Ma S. Overcoming challenges for the economic evaluation of investments in children’s health. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9(3):136-137.

- 13. Griebsch I, Coast J, Brown J. Quality-adjusted life-years lack quality in pediatric care: a critical review of published cost-utility studies in child health. Pediatrics. 2005;115(5):E600-E614.

- 14. Bouwmans CAM, Schawo SJ, Hakkaart-van Roijen L. Handleiding Vragenlijst TiC-P voor kinderen. Rotterdam: Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam, iMTA 2012.

- 15. Homer JF, Drummond MF, French MT. Economic evaluation of adolescent addiction programs: methodologic challenges and recommendations. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(6):529-539.

- 16. Kilian R, Losert C, Lark AL, McDaid D, Knapp M. Cost-effectiveness analysis in child and adolescent mental health problems: an updated review of literature. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2010;12:45-57.

- 17. Knapp M. Economic evaluations and interventions for children and adolescents with mental health problems. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38(1):3-25.

- 18. Knapp M, Evans-Lacko S. Health economics. In: Thapar A, et al. Rutter’s child and adolescent psychiatry. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell 2015.

- 19. Koot HM. Challenges in child and adolescent quality of life research. Acta Paediatrica. 2002;91(3):265-266.

- 20. Matza LS, Swensen AR, Flood EM, Secnik K, Leidy NK. Assessment of health-related quality of life in children: a review of conceptual, methodological, and regulatory issues. Value Health. 2004;7(1):79-92.

- 21. Pal DK. Quality of life assessment in children: a review of conceptual and methodological issues in multidimensional health status measures. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1996;50(4):391-396.

- 22. Petrou S. Methodological issues raised by preference-based approaches to measuring the health status of children. Health Economics. 2003;12(8):697-702.

- 23. Prosser LA, Hammitt JK, Keren R. Measuring health preferences for use in cost-utility and cost-benefit analyses of interventions in children - theoretical and methodological considerations. Pharmacoeconomics. 2007;25(9):713-726.

- 24. Thorn JC, Coast J, Cohen D, et al. Resource-use measurement based on patient recall: issues and challenges for economic evaluation. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2013;11(3):155-161.

- 25. Ungar WJ. Challenges in health state valuation in paediatric economic evaluation are QALYs contraindicated? Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29(8):641-652.

- 26. Wallander JL, Schmitt M, Koot HM. Quality of life measurement in children and adolescents: issues, instruments, and applications. J Clin Psychol. 2001;57(4):571-585.

- 27. Woolderink M, Lynch FL, van Asselt AD, et al. Methodological considerations in service use assessment for children and youth with mental health conditions; issues for economic evaluation. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(3):296-308.

- 28. Zavala SK, French MT, Henderson CE, Alberga L, Rowe C, Liddle HA. Guidelines and challenges for estimating the economic costs and benefits of adolescent substance abuse treatments. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;29(3):191-205.

- 29. Bouwmans CAM, Schawo SJ, Jansen DEMC, Vermeulen K, Reijneveld M, Hakkaart-van Roijen L. Handleiding Vragenlijst Intensieve Jeugdzorg: Zorggebruik en productieverlies. Rotterdam: Erasmus Universitiet Rotterdam 2012.

- 30. Delwel GO. Leidraad voor Uitkomstenonderzoek ‘ten behoeve van de beoordeling doelmatigheid intramurale geneesmiddelen’ Op 1 december 2008 vastgesteld en uitgebracht aan de Minister van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport. Delwel: College voor zorgverzekeringen 2008.

- 31. Drost R, Paulus ATG, Ruwaard D, Evers SMMA. Handleiding intersectorale kosten en baten van (preventieve)interventies. Maastricht: Universiteit Maastricht 2014.

- 32. Romijn G, Renes G. Algemene leidraad voor maatschappelijke kosten-batenanalyse. Den Haag: Centraal Planbureau/Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving 2013.

- 33. Pomp M, Schoemaker CG, Polder JJ. Themarapport Volksgezondheid Toekomst Verkenning (VTV). Op weg naar maatschappelijke kosten-baten analyses voor preventie en zorg. Bilthoven: Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu 2014.

- 34. Ravens-Sieberer U, Wille N, Badia X, et al. Feasibility, reliability, and validity of the EQ-5D-Y: results from a multinational study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(6):887-897.

- 35. Wille N, Badia X, Bonsel G, et al. Development of the EQ-5D-Y: a child-friendly version of the EQ-5D. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(6):875-886.

- 36. Zorginstituut Nederland. Kostenhandleiding: Methodologie van kostenonderzoek en referentieprijzen voor economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg. Diemen: Zorginstituut Nederland 2015.

- 37. Zorginstituut Nederland. Richtlijn voor het uitvoeren van economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg. Diemen: Zorginstituut Nederland 2015.

- 38. Mierau JO, Kann-Weedage D, Hoekstra PJ, et al. Assessing quality of life in psychosocial and mental health disorders in children: a comprehensive overview and appraisal of generic health related quality of life measures. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20(1):329.

- 39. Netherlands Youth Institute. https://www.nji.nl/nl/Kennis/Dossier/Effectieve-jeugdhulp/Kosteneffectiviteit.