|

Arch Physioter 2024; 14: 189-195 ISSN 2057-0082 | DOI: 10.33393/aop.2024.3370 MASTERCLASS |

|

Integrating spirituality into physical therapy: exploring its emerging role as a recognized determinant of health

ABSTRACT

This masterclass explores the increasing recognition of spirituality as a vital aspect of patient care, alongside other Social Determinants of Health (SDH) such as economic stability and education. The distinction between spirituality and religion is clarified, with spirituality described as a broader, more personal experience that can exist both within and outside of religious contexts. Research demonstrates that spirituality influences health in mostly positive ways, particularly in areas like mental health, resilience, and coping, making it a critical component of holistic, patient-centered care. In physical therapy, incorporating a patient’s spirituality into their plan of care can enhance cultural competence and foster a more holistic care approach. However, many Physical Therapists (PTs) express uncertainty in addressing spiritual concerns, often due to limited training or unclear role expectations. The authors suggest that integrating tools like the Inclusive Spiritual Connection Scale (ISCS), Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp), Spiritual Well-Being Questionnaire (SWBQ), the Spiritual Health and Life-Orientation Measure (SHALOM), or the Spiritual Transcendence Scale (STS), along with enhanced education, could help therapists incorporate spirituality into practice more seamlessly. Integration of spirituality enables PTs to deliver more complete, personalized care that addresses the whole person. Ultimately, the authors advocate for recognizing spirituality as a key determinant of health and an important component of healthcare to ensure more inclusive treatment.

Keywords: Cultural competency, Physical therapy, Spirituality

Received: November 5, 2024

Accepted: December 30, 2024

Published online: December 31, 2024

Corresponding author:

Alessandra N. Garcia

email: alessandra.garcia.pt@gmail.com

Archives of Physiotherapy - ISSN 2057-0082 - www.archivesofphysiotherapy.com

© 2024 The Authors. This article is published by AboutScience and licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0).

Commercial use is not permitted and is subject to Publisher’s permissions. Full information is available at www.aboutscience.eu

Background

“A closed mouth can’t get fed… They have to know a little bit about your circumstances to be able to help you”, was a response from a participant in a qualitative study when asked about their perception of how social factors may be relevant to their healthcare (1). Their comment highlights the importance of recognizing and addressing individual social factors in patient care, reflecting the growing emphasis in healthcare on integrating SDH into clinical practice. In recent years, there has been growing recognition of the critical role that SDH, such as education, economic stability, and neighborhood environment, play in shaping well-being, health outcomes, and health-related behaviors (2).

Similarly, spirituality, like social and economic factors, is being recognized as vital in shaping patient well-being (3,4). Although not yet regarded on the same level, there is growing recognition of the effort to fully integrate spirituality into healthcare and consider it an important SDH (5,6). As this awareness grows, healthcare providers are more frequently encouraged to consider spirituality as part of comprehensive care, especially in disciplines like physical therapy, where patient-centered approaches are crucial (5,7). In this masterclass, we explore the concept of spirituality and its domains, as well as spirituality as a potential determinant of health. We also review evidence of spirituality’s impact on health outcomes, explore its implications for physical therapy practice and education, and present practical examples of incorporating spirituality into clinical practice with an emphasis on assessment and measurement tools.

Spirituality

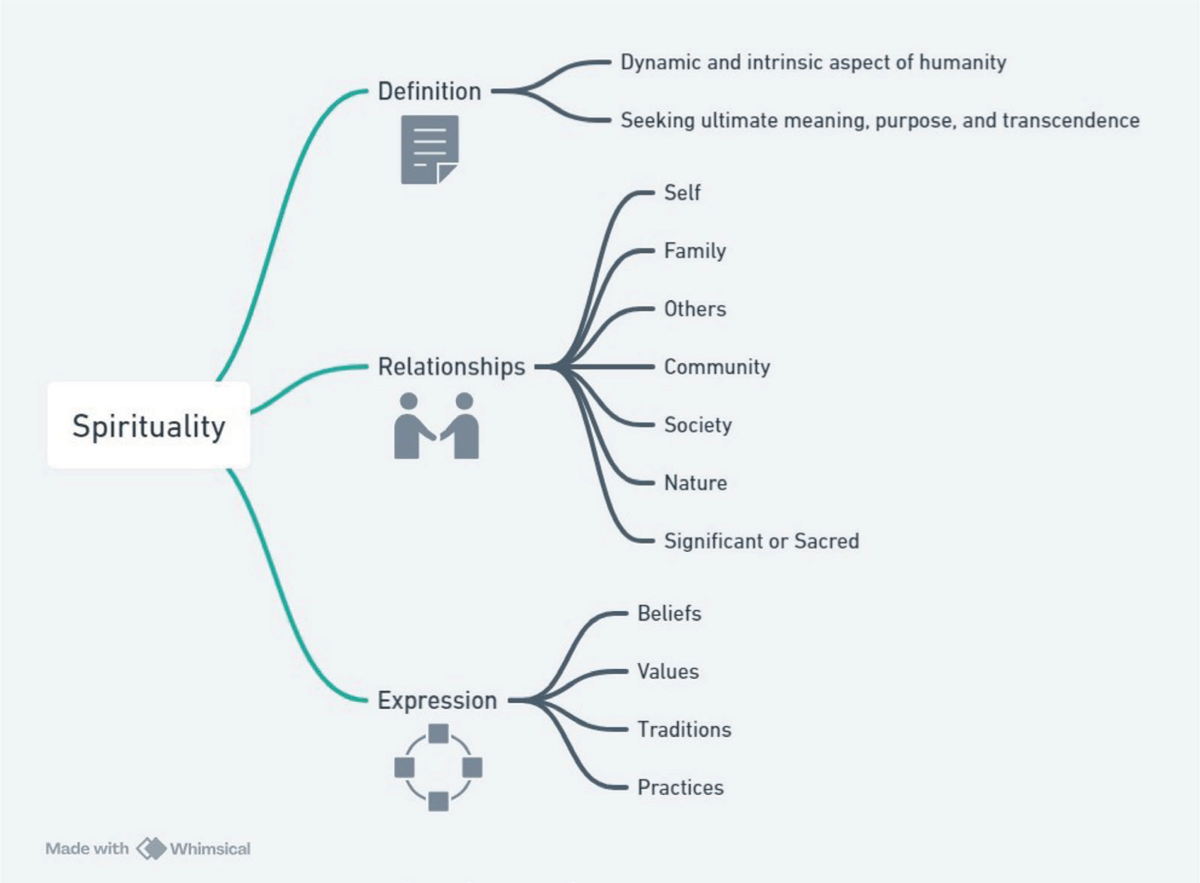

Although often used interchangeably, spirituality and religion are multidimensional concepts that represent distinct ideas. The definition of spirituality varies across academic disciplines, and the dimensions assessed in different studies are often inconsistent (6,8). Spirituality can be defined as “a dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity through which persons seek ultimate meaning, purpose, and transcendence and experience relationship to self, family, others, community, society, nature, and the significant or sacred. Spirituality is expressed through beliefs, values, traditions, and practices.” (5,9) (Fig. 1) Religion, by contrast, names “the search for significance that occurs within the context of established institutions that are designed to facilitate spirituality.” (5,6,9,10) In this sense, spirituality can be viewed as a broader concept than religion, encompassing an individual’s search for and connection with what they perceive as transcendent or sacred (11-14). Religion, on the other hand, serves as one potential pathway for this search and connection. While spirituality often describes personal experiences and beliefs within a religious framework, it can also extend beyond specific traditions or faith communities, as reflected in the popular expression “spiritual but not religious.” (15)

FIGURE 1 - Concept of spirituality

Both religion and spirituality encompass significant social dimensions (16). Religion often fosters community through shared practices, traditions, and institutions, providing a sense of belonging and collective identity. Spirituality, while more individualized, can also create social bonds by encouraging connections with others through shared values, mutual support, and collective experiences of meaning and purpose. These social aspects may contribute to the overall well-being of individuals by offering support networks and a sense of community (17). The past fifty years of research have tended to emphasize four domains of spirituality: personal, communal, environmental, and transcendental (18). Examples of practices that nurture personal domains, exemplify community and the search for spiritual relatedness, access the environmental domain, and manifest the transcendental domain are outlined in Table 1.

| Personal Domain | Communal | Environmental | Transcendental |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contemplation, prayer, meditation | Church or community gathering attendance | Spending time in nature (walking, hiking, camping, gardening, boating) | Breathing exercises and meditation |

| Scripture/spiritual reading | Shared meals | Volunteering for roadside clean-up | Prayer and worship of the Divine |

| Chanting, recitation | Communal singing, rituals & sacraments | Contributing to recycling efforts | The study of holy texts |

| Activities that affirm one’s sense of identity and help bring about self-awareness (e.g., sound/energy healing) | Acts of community service | Tai chi, qigong | Similar practices evoke a sense of peace and oneness with God and the Divine |

Spirituality: A Domain of Health and Wellness and a Potential Determinant of Health

Spirituality is a vital domain of health and wellness for person-centered care (7,19,20). Person-centered care, as opposed to patient-centered care, takes a holistic approach to healing body, mind, and spirit that supports PTs in developing more individualized treatment plans to enhance overall health and well-being (3,4). In this context, ‘spiritual health’ is defined as “a state of being in which an individual effectively manages life’s challenges, leading to the realization of one’s full potential, meaning, and purpose, and fulfillment from within.” (4) Additionally, ‘spiritual wellness’ may be understood as “a positive sense of meaning and purpose in life” (3) or “the development of an appreciation for the depth and expanse of life and natural forces that exist in the universe.” (21)

In other words, spiritual wellness can be considered an integral component of holistic health, with spirituality serving as a primary driver. Health comprises physical, psychological, emotional, social, and spiritual dimensions, all of which interact and influence one another (4). Despite the importance of each element, spirituality remains underrepresented in research and is less extensively documented (6,9). At the very least, evidence suggests spirituality can have a mediating role, linking other health determinants to outcomes. But it is also becoming clear that spirituality has a broader influence on well-being (6,9). More recently, Delphi panels, consisting of clinicians, public health experts, researchers, health system leaders, and medical ethicists, have recommended recognizing spirituality as a ‘determinant of health’, alongside other social factors, due to its demonstrated influence on health outcomes, which will be discussed further (9).

Impact of Spirituality on Health Outcomes

The distinction between religion and spirituality intersects with health outcomes in complex ways, and existing research provides far more insight into the relationship between religion and health than spirituality and health. This discrepancy might stem from the fact that while there are standardized methods for measuring religious beliefs and practices, fewer such means exist for assessing spirituality, in part because spirituality is so often highly individualized. While numerous operational definitions of spirituality exist across disciplines, studies that isolate spirituality as a distinct construct, separate from religion or psychological well-being, are comparatively limited.

A systematic review based on high-quality evidence and expert analysis (9) identified various secular and religious dimensions of spirituality, such as community involvement and prayer, that may be linked to health outcomes. For example, the frequency of attendance at religious services was associated with a reduced mortality risk. Additionally, those who attended services more frequently exhibited lower rates of smoking, alcohol use, marijuana use, and illicit drug use compared to individuals with less frequent or no attendance. The frequency of attendance at religious services was also connected to better quality of life, including higher life satisfaction, improved mental health, fewer depressive symptoms, and reduced suicidal behaviors. Among adolescents, frequent attendance was associated with lower levels of unsafe sexual behavior, smoking, and substance use, including alcohol, marijuana, and illicit drugs. While most existing literature on spirituality and health situates spirituality within a religious framework, (22) we continue to see similar patterns of connection between secular spiritual expressions and positive health outcomes. For example, spiritual well-being and secular reverence have been associated with reduced levels of cardiovascular risk markers and shorter hospital stays after open-heart surgery, respectively (23,24).

Spiritual practices and beliefs can serve as coping mechanisms for stress and anxiety, but they can also help reorient people’s perspectives and help them develop attitudes of resiliency and positivity. Gathering together a broad survey of studies, Mueller, Plevak, and Rummans found that spiritual practice and spiritual well-being are associated with more positive outlooks in persons with “cancer, HIV disease, heart disease, limb amputation, and spinal cord injury.” (25) Religious practice serves as a helpful coping mechanism for people with asthma, anxiety, and feelings of stress. Spirituality does not, of course, guarantee better health outcomes. In a review of 3,300 empirical studies on religiosity and spirituality, approximately 12% of the studies reported negative associations between spirituality/religiosity (e.g., spiritual struggle or distress) and various health outcomes (e.g., general well-being, depression, anxiety, cancer) (26).

It is important to note that the benefits attributed to the religious dimensions of spirituality, as previously discussed, may also stem from the inherently social nature of religious institutions (e.g., churches, mosques, synagogues, and temples). These institutions often provide social support, opportunities for interaction, and community activities (27). Nearly nine out of ten U.S. adults (89%) believe religious institutions foster community connection and unity (27). Similarly, 87% recognize their significant role in assisting the poor and vulnerable, while three-quarters credit them with upholding and promoting societal morality (27). 90% or more of Christians, along with 88% of Muslims, Jews, and Hindus, regard religious institutions as unifying forces in society (27). Non-religious individuals also recognize this role, including 85% of agnostics, 81% of those without a specific religious identity, and 75% of atheists (27). Similarly, most Christians (90%), adherents of non-Christian faiths (82%), and religiously unaffiliated individuals (78%) agree that religious institutions play a crucial role in supporting the poor and needy (27).

Spiritual and religious values can, at times, amplify fear, refusal of treatment, and distrust of medical institutions and practitioners. For example, religious affiliation may be linked to vaccine hesitancy rates in certain religious communities (28,29) and negative mental health effects because of shame and guilt associated with uncured illnesses (30). In addition, while many Americans acknowledge the positive societal contributions of religious institutions, roughly half also voice concerns about their behavior. These concerns include being overly focused on money and power, excessively rule-driven, and too involved in political matters (27).

Implications of Spirituality for Physical Therapy Practice, and Education

Incorporating spirituality into physical therapy practice holds significant implications for practice and education. The integration of spirituality can enhance patient-centered care, promote holistic healing, and improve overall treatment adherence. These implications will be explored in greater detail throughout the discussion.

Physical Therapy Practice Implications

Spirituality, as a source of personal meaning and values, may play a critical role in delivering person-centered care and promoting cultural competence in physical therapy (7,9,31,32). A culturally competent system can deliver more holistic and effective care by adhering to key values and principles that focus on designing and implementing services tailored to the unique needs of individuals, children, and families (33). A culturally competent system requires understanding a person or family’s cultural identity, as well as their levels of assimilation, in order to effectively apply the principle of “starting where the individual or family is.” (33) Additionally, cultural competence involves collaborating with natural and informal support networks within diverse communities, such as neighborhood organizations, civic and advocacy groups, ethnic and social organizations, religious institutions, and, where appropriate, spiritual healers (33). Recognizing the role of spirituality within these networks is crucial, as it often forms a vital component of cultural identity and well-being.

It is worth noting that cultural competence is a fundamental aspect of the American Physical Therapy Association’s (APTA) vision to ‘transform society by optimizing movement to improve the human experience.’ (33) Several of APTA’s guiding principles for achieving this vision are directly linked to cultural competence (33). For example, ‘consumer-centricity’ emphasizes the need for PTs to prioritize patient values, goals, and individual needs in care, which includes recognizing cultural (including spiritual) factors (33). ‘Access/equity’ focuses on addressing health disparities and SDHs through innovative and inclusive care models, which may involve considering patients’ spiritual beliefs (33). ‘Advocacy’ highlights the role of PTs in promoting patient-centered care by driving change in healthcare systems (33). Integrating spirituality into these principles ensures holistic, culturally competent care that respects and responds to patients’ diverse backgrounds (33).

In addition, research indicates that addressing the spiritual needs of patients in healthcare can enhance patients’ psychological well-being and satisfaction with care (34). This aligns with the biopsychosocial model, which emphasizes the importance of addressing psychological and social factors alongside physical health (35). Recognizing the spiritual dimensions of health allows PTs to create more comprehensive treatment plans that resonate with patients’ values and beliefs. Moreover, spiritual considerations can foster better therapeutic relationships. When PTs engage with patients on a spiritual level, it cultivates trust and openness, facilitating more effective communication (36). This can lead to increased motivation and adherence to treatment plans, as patients feel more understood and supported (37).

In clinical practice, it is not uncommon for patients and therapists to hold differing beliefs, including those related to spirituality, its meaning, and its implications. When such differences arise, it is crucial for PTs to cultivate self-awareness, which means acknowledging one’s own spirituality in a way that does not presume anything about the patient’s spirituality or impose anything on the patient. In addition, it is crucial for PTs to broaden their appreciation for diverse expressions of faith and spirituality in their patients. This can be done through didactic training and hands-on experience (33). While PTs do not provide direct spiritual care, they should be prepared to respectfully acknowledge and support a patient’s spiritual framework as it intersects with their physical therapy journey (33). For specific spiritual needs, similar to other SDH that fall outside the scope of physical therapy, PTs can refer patients to qualified professionals such as chaplains, spiritual care providers, religious leaders (e.g., priests, pastors, imams, or rabbis), spiritual counselors, or mental health professionals with expertise in spirituality (38). These referrals ensure patients receive appropriate support tailored to their beliefs and needs (38).

Educational Implications

The integration of spirituality in physical therapy education is crucial for preparing future practitioners to address the diverse needs of their patients. Current curricula often lack comprehensive training on spiritual care, which can lead to discomfort or inadequacy in handling these topics in practice (39). However, evidence has demonstrated the role of spirituality in patients’ ability to reshape and interpret life events, as a coping mechanism, as a tool for pain management, and as a part of wellness and cultural competence (40). Educators are encouraged to incorporate spirituality into existing courses to ensure that learning experiences are intentional and address their role in patient care, ethical considerations, and therapeutic alliance. Furthermore, training programs that include reflective practices on spirituality can enhance students’ self-awareness and empathy (41). This not only prepares students to engage more effectively with patients but also promotes their own well-being, helping to mitigate burnout and compassion fatigue often experienced in the healthcare field (42).

Relatedly, part of the curriculum should address religious trauma, including how to recognize it in oneself as a clinician and in one’s patients, and what resources are available to navigate it. A large study published in 2023 gave evidence that as many as 1 in 5, or 20%, of U.S. adults, have suffered or are suffering from hurtful and harmful experiences with religion. At the very least, PTs need to be trained to approach the subject of spirituality with sensitivity and empathy, allowing the patient to lead and articulate the terms of engagement (43).

Examples of how to Incorporate Spirituality into Clinical Practice: Focus on Assessment and Measures

To our knowledge, there is no universally accepted “best” method for incorporating spirituality into clinical practice, as effective integration depends on the specific context, individual patient needs, and provider expertise. Nevertheless, best practices generally encompass a combination of comprehensive assessment, clear communication, and personalized interventions that respect and align with patients’ beliefs and values. This section highlights key gaps in integrating spirituality into clinical practice, offers examples of how PTs can assess and measure patients’ spirituality, and describes a systematic review with consensus-suggested implications for how to address spirituality in serious illness and health outcomes (9).

Despite the guidance of the APTA and the plethora of literature supporting the need to incorporate a patient’s spirituality into their session, PTs may not be incorporating these principles into their plan of care (44). Research shows (44) that while 96% of PTs believe spiritual well-being is a vital component of health, only 30% feel that addressing spiritual concerns falls within their responsibilities. That leads to the question of whose role it is to address spirituality in healthcare. Secondly, what barriers do PTs encounter if and when they address spirituality? Research findings also revealed a lack of education in taking spiritual history and navigating spiritual beliefs. This raises another question: What is the PT’s obligation in terms of moral responsibility, code of ethics, and policy to address the patient’s spirituality in the plan of care?

Similar to physical therapy, other healthcare disciplines recognize a gap in their integration of spiritual assessment in patient care (e.g., The Joint Commission and the American College of Physicians) (7,45). The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) requires the administration of a spiritual assessment as of 2001. JCAHO’s requirements address three areas (1) important spiritual practices, (2) denomination or faith tradition, and (3) significant spiritual beliefs with a list of questions to help guide the clinician in the assessment. Allowing the patient to answer neutrally is the goal of the JCAHO to assist with respecting the individual’s spirituality. With this knowledge, JCAHO mandates healthcare organizations, including those with physical therapy, to take into consideration the spiritual needs of the patient and the barriers to creating a policy that is consistent across the field.

Balboni et al. highlighted that the limited provision of spiritual care for patients with serious illnesses is partly due to care team members not adequately addressing patient spirituality (9). Screening for spiritual needs is frequently overlooked, possibly due to time constraints, a belief that addressing spirituality falls outside the clinician’s responsibilities, or discomfort in discussing such topics with patients (9), as well as due to concerns about provider competence and/or patient vulnerability in the medical environment (7). In clinical practice, clinicians may incorporate brief assessments to perform initial screenings that address spiritual care (9). This may include asking straightforward spiritual history questions such as, “Is spirituality or faith important to you in relation to your health and illness?” or “Do you have, or would you like, someone to talk to about spiritual or faith matters?” (9) This approach ensures that spiritual needs are integrated into comprehensive patient care and reflects respect for the patient’s spiritual values (9).

Other examples of spirituality measures include multidimensional scales, such as the Bio-psycho-socio-spiritual Inventory (BioPSSI), Perceived Wellness Survey (PWS), Positive Mental Health Measurement Scale (PMH), and the WHOQOL-100 (46). Examples of questionnaires that more directly and comprehensively assess spirituality include the ISCS, (22,47) Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness FACIT-Sp, (12,48) SWBQ, (49,50) the SHALOM (51), and the STS (52).

The ISCS assesses levels of spiritual connection within spiritually diverse populations and is designed for use with clients in healthcare settings (22,47). It is a unidimensional scale consisting of 13 items tapping into the level and centrality of spiritual connection (22,47). It also contains 1 frame of reference item in which clients indicate the source of their spiritual connection (e.g., nature, God/Allah, multiple gods, and the universe) (22,47). The frame of reference items allows clinicians to quickly and directly understand if spirituality is important to their client and if so, the source of their clients’ spiritual connection (22,47). This item has the capacity to reduce provider discomfort and increase client agency within the exchange (22,47). ISCS is grounded in theory, operationalizes spirituality from an expansive framework, utilizes inclusive language, and demonstrates strong psychometric properties (22,47). With a growing portion of US adults engaging in diverse spiritual expressions, the ISCS allows for a more inclusive assessment approach (53).

The FACIT-Sp is a cross-culturally validated measure designed to assess a patient’s state of spiritual well-being, utilizing a multidimensional framework (48). It consists of 12 items with a Likert-type response scale and contains a subscale (Meaning and Peace) designed to assess spirituality from a more expansive framework (48). FACIT-Sp is a useful measure if the assessment of current spiritual well-being state is desired (in contrast to measurement of spiritual well-being as a trait), (48) as it frames questions based on the respondents’ last 7 days (22).

Both the SWBQ and SHALOM instruments are available in multiple languages and have validated measurement properties (49-51). The SWBQ is a 20-item tool that assesses four key dimensions of spirituality: personal (reflecting one’s internal sense of meaning, purpose, and values), communal (focused on the quality of interpersonal relationships, including love, justice, and hope), environmental (concerned with the individual’s connection to nature and the environment), and transcendental (addressing beliefs in and relationships with a higher power, such as God, and the associated faith, adoration, and worship) (49,50).

The SHALOM (51) consists of two sets of 20 items, identical to those in the SWBQ. In the first set, respondents are asked to indicate what they believe the ideal levels for each descriptor should be (the “ideal” component) (51). In the second set, they are asked to rate how the descriptors reflect their own experiences over the past six months (the “lived experience” component) (51). In contrast to the SWBQ, which assesses spirituality by evaluating current states or traits without comparing them to ideal levels, the SHALOM incorporates both ideal and lived experiences. This allows for a comparison between an individual’s spiritual aspirations and their actual experiences, helping to identify gaps in spiritual well-being (49-51).

Lastly, the STS is a 24-item measure designed to assess spirituality as an expansive and central element of the human experience (52). The measure utilizes a 5-point Likert-type response scale across three subscales (connectedness, universality, and prayer fulfillment) (52). Evidence of adequate internal consistency and convergent validity has been demonstrated (52). A unique aspect of the STS is the peer evaluation form that can be completed concurrently. The STS peer evaluation form provides an avenue for engaging core social support figures in a client’s holistic health journey.

In 2022, a systematic review and multidisciplinary Delphi panel (9) recommended six implications, three for addressing spirituality in serious illness and three for addressing spirituality in health outcomes. The primary implications, supported by strong evidence, for how to address spirituality in serious illness were: “(1) incorporate spiritual care into care for patients with serious illness; (2) incorporate spiritual care education into training of interdisciplinary teams caring for persons with serious illness; and (3) include specialty practitioners of spiritual care in care of patients with serious illness.” The primary implications, supported by strong evidence, for how to address spirituality in health outcomes were: “(1) incorporate patient-centered and evidence-based approaches regarding associations of spiritual community with improved patient and population health outcomes; (2) increase awareness among health professionals of evidence for protective health associations of spiritual community; and (3) recognize spirituality as a social factor associated with health in research, community assessments, and program implementation.” This systematic review was based on high-quality evidence and expert appraisal, and the referenced recommendations underscore the importance of integrating spirituality into healthcare practice, education, and research to enhance patient care and health outcomes.

Conclusion

Incorporating spirituality into physical therapy practice has significant implications for enhancing patient care and addressing diverse health outcomes. A holistic approach that includes the spiritual dimension allows clinicians to address the complex needs of their patients more effectively, leading to improved health outcomes and greater patient satisfaction. Recognizing spirituality as a key determinant of health supports the development of treatment plans that align with patients’ values, fostering stronger therapeutic relationships. As the field of physical therapy evolves, integrating spirituality into both clinical practice and educational curricula will be essential for providing compassionate, culturally competent care. This holistic perspective may not only enhance patient care but can also enable PTs to connect with their patients on a deeper level, potentially fostering resilience. A variety of spirituality assessment tools, such as ISCS, FACIT-Sp, SWBQ, SHALOM, and STS, provide healthcare providers with comprehensive frameworks for evaluating spiritual well-being, ensuring a more inclusive and personalized approach to meeting patients’ diverse spiritual needs.

Disclosures

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest

Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors’ Contributor Role: AG and AE were responsible for the conceptualization of the study. All authors participated in writing the manuscript and critically revised it for important intellectual content. The final manuscript was approved by all authors, who have read and agreed to the published version.

Data Availability Statement: Data sharing not applicable.

References

- 1. Kiles TM, Cernasev A, Leibold C, et al. Patient perspectives of discussing social determinants of health with community pharmacists. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2022;62(3):826-833. CrossRef

- 2. Rethorn ZD, Cook C, Reneker JC. Social Determinants of Health: If You Aren’t Measuring Them, You Aren’t Seeing the Big Picture. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2019;49(12):872-874. CrossRef PubMed

- 3. Bezner JR. Promoting Health and Wellness: Implications for Physical Therapist Practice. Phys Ther. 2015;95(10):1433-1444. CrossRef PubMed

- 4. Dhar N, Chaturvedi SK, Nandan D. Spiritual health, the fourth dimension: a public health perspective. WHO South-East Asia J Public Health. 2013;2(1):3-5. CrossRef PubMed

- 5. Puchalski CM, Vitillo R, Hull SK, et al. Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: reaching national and international consensus. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(6):642-656. CrossRef PubMed

- 6. Long KNG, Symons X, VanderWeele TJ, et al. Spirituality As A Determinant Of Health: Emerging Policies, Practices, And Systems. Health Aff (Millwood). 2024;43(6):783-790. CrossRef PubMed

- 7. Pearce MJ. Addressing religion and spirituality in health care systems. In: An Applied Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. APA handbooks in psychology. American Psychological Association; 2013:527-541. APA Handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality; vol 2., CrossRef.

- 8. Idler E, Idler EL, eds. Religion: The Invisible Social Determinant. In: Religion as a Social Determinant of Public Health. Oxford University Press; 2014:0. CrossRef

- 9. Balboni TA, VanderWeele TJ, Doan-Soares SD, et al. Spirituality in Serious Illness and Health. JAMA. 2022;328(2):184-197. CrossRef PubMed

- 10. Oman D. Defining religion and spirituality. In: Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2nd ed. The Guilford Press; 2013:23-47. Online (Accessed November 2024)

- 11. Paul Victor CG, Treschuk JV. Critical Literature Review on the Definition Clarity of the Concept of Faith, Religion, and Spirituality. J Holist Nurs. 2020;38(1):107-113. CrossRef PubMed

- 12. Monod S, Brennan M, Rochat E, et al. Instruments measuring spirituality in clinical research: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(11):1345-1357. CrossRef PubMed

- 13. Pargament KI, ed. Searching for the sacred: Toward a nonreductionistic theory of spirituality. In: APA Handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality (Vol 1): Context, Theory, and Research. APA handbooks in psychology®. American Psychological Association; 2013:257-273. CrossRef

- 14. Sessanna L, Finnell DS, Underhill M, et al. Measures assessing spirituality as more than religiosity: a methodological review of nursing and health-related literature. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(8):1677-1694. CrossRef PubMed

- 15. Kallo BAA Michael Rotolo, Patricia Tevington, Justin Nortey, et al. Who are ‘spiritual but not religious’ Americans? Pew Research Center. December 7, 2023. Online (Accessed November 2024)

- 16. Cox D. Religion, the Spiritual Dimension and Social Development. In: Midgley J, Pawar M, eds. Future Directions in Social Development. 2017:187-204, CrossRef.

- 17. Villani D, Sorgente A, Iannello P, et al. The Role of Spirituality and Religiosity in Subjective Well-Being of Individuals With Different Religious Status. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1525. CrossRef PubMed

- 18. Fisher J. Development and Application of a Spiritual Well-Being Questionnaire Called SHALOM. Religions (Basel). 2010;1(1):105-121. CrossRef

- 19. Gang JA, Gang GR, Gharibvand L. Integration of Spirituality and Whole Person Care into Doctor of Physical Therapy Curricula: A Mixed Methods Study. J Allied Health. 2022;51(2):130-135. PubMed

- 20. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. Spirit & Soul – Whole Health. Online (Accessed November 2024)

- 21. National Wellness – National Wellness Institute. March 18, 2020. Online (Accessed November 2024)

- 22. Hoots VM. Conceptualization and Measurement of Spirituality: Towards the Development of a Nontheistic Spirituality Measure for Use in Health-Related Fields. Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Published online December 1, 2017. Online (Accessed November 2024)

- 23. Ai AL, Wink P, Shearer M. Secular reverence predicts shorter hospital length of stay among middle-aged and older patients following open-heart surgery. J Behav Med. 2011;34(6):532-541. CrossRef PubMed

- 24. Holt-Lunstad J, Steffen PR, Sandberg J, et al. Understanding the connection between spiritual well-being and physical health: an examination of ambulatory blood pressure, inflammation, blood lipids and fasting glucose. J Behav Med. 2011;34(6):477-488. CrossRef PubMed

- 25. Mueller PS, Plevak DJ, Rummans TA. Religious involvement, spirituality, and medicine: implications for clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(12):1225-1235. CrossRef PubMed

- 26. Koenig HG. Religion, spirituality, and health: a review and update. Adv Mind Body Med. 2015;29(3):19-26. PubMed

- 27. Wormald B. Chapter 3: Views of Religious Institutions. Pew Research Center. November 3, 2015. Online (Accessed November 2024)

- 28. Tiwana MH, Smith J. Faith and vaccination: a scoping review of the relationships between religious beliefs and vaccine hesitancy. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):1806. CrossRef PubMed

- 29. Alsuwaidi AR, Hammad HAA, Elbarazi I, et al. Vaccine hesitancy within the Muslim community: islamic faith and public health perspectives. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2023;19(1):2190716. CrossRef PubMed

- 30. Bowler K. A History of the American Prosperity Gospel. Oxford University Press; 2013. CrossRef

- 31. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academies Press (US); 2001. Online (Accessed November 2024)

- 32. APTA. Cultural Competence in Physical Therapy. Online (Accessed November 2024)

- 33. APTA. Achieving Cultural Competence. January 15, 2020. Accessed September 16, 2024. Online (Accessed November 2024)

- 34. Hodge DR. Administering a two-stage spiritual assessment in healthcare settings: a necessary component of ethical and effective care. J Nurs Manag. 2015;23(1):27-38. CrossRef PubMed

- 35. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129-136. CrossRef PubMed

- 36. Giske T, Cone P. Comparing Nurses’ and Patients’ Comfort Level with Spiritual Assessment. Religions (Basel). 2020;11(12):671. CrossRef

- 37. de Brito Sena MA, Damiano RF, Lucchetti G, et al. Defining Spirituality in Healthcare: A Systematic Review and Conceptual Framework. Front Psychol. 2021;12:756080. CrossRef PubMed

- 38. APTA. APTA Guide for Professional Conduct. Online (Accessed November 2024)

- 39. Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(10):885-904. CrossRef PubMed

- 40. Sargeant DM. Teaching Spirituality in the Physical Therapy Classroom and Clinic. J Phys Ther Educ. 2009;23(1):29-35. CrossRef

- 41. Gonçalves JPB, Lucchetti G, Menezes PR, et al. Religious and spiritual interventions in mental health care: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Psychol Med. 2015;45(14):2937-2949. CrossRef PubMed

- 42. Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clin Psychol (New York). 2003;10(2):144-156. CrossRef

- 43. Slade D, Smell A, Wilson E, et al. Percentage of U.S. Adults Suffering from Religious Trauma. SHERM Journal. 2023. Online (Accessed November 2024)

- 44. Oakley ET, Sauer K, Dent B, et al. Physical Therapists’ Perception of Spirituality and Patient Care: Beliefs, Practices, and Perceived Barriers. J Phys Ther Educ. 2010;24(2):45-52. CrossRef

- 45. Hodge DR. A template for spiritual assessment: a review of the JCAHO requirements and guidelines for implementation. Soc Work. 2006;51(4):317-326. CrossRef PubMed

- 46. Lindert J, Bain PA, Kubzansky LD, et al. Well-being measurement and the WHO health policy Health 2010: systematic review of measurement scales. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(4):731-740. CrossRef PubMed

- 47. Hoots V. Measurement of Nontheistic and Theistic Spirituality: Initial Psychometric Qualities of the Inclusive Spiritual Connection Scale. Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Published online December 1, 2020. Online (Accessed November 2024)

- 48. Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, et al. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy--Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med. 2002;24(1):49-58. CrossRef PubMed

- 49. Gomez R, Watson S. A Reevaluation of the Factor Structure, Reliability, and Validity of the Spiritual Well-Being Questionnaire (SWBQ). J Relig Health. 2023;62(3):2112-2130. CrossRef PubMed

- 50. Gomez R, Fisher JW. Domains of spiritual well-being and development and validation of the Spiritual Well-Being Questionnaire. Pers Individ Dif. 2003;35(8):1975-1991. CrossRef

- 51. Fisher JW. Validation and Utilisation of the Spiritual Well-Being Questionnaire: SHALOM. J Relig Health. 2021;60(5):3694-3715. CrossRef PubMed

- 52. Piedmont RL. Does Spirituality Represent the Sixth Factor of Personality? Spiritual Transcendence and the Five-Factor Model. J Pers. 1999;67(6):985-1013. CrossRef

- 53. Kallo BAA Michael Rotolo, Patricia Tevington, Justin Nortey, et al. Spirituality Among Americans. Pew Research Center. December 7, 2023. Online (Accessed November 2024)