|

AboutOpen | 2024; 11: 4-7 ISSN 2465-2628 | DOI: 10.33393/ao.2024.2730 POINT OF VIEW |

|

After 100 years of life, is there an insulin crisis? The problem of insulin costs and the opportunity of biosimilar insulins

ABSTRACT

Considering other pharmacological approaches, also in the field of insulin therapy, the use of biosimilar drugs instead of originators could help to reduce the worldwide increasing costs of its related disease, that is, diabetes mellitus (DM), and the subsequent risk of insulin underutilization. Available evidences clearly demonstrate that biosimilar efficacy and safety are superimposable to those of the originator insulin with lower expenditure; despite this, however, their underutilization persists both in Eastern and in Western countries. Specific, regional activities are needed in order to improve biosimilar insulin use and to contribute to a substantial reduction of the costs of DM.

Keywords: Biosimilar insulin, Diabetes mellitus, Insulin costs

Received: November 20, 2023

Accepted: January 29, 2024

Published online: February 9, 2024

AboutOpen - ISSN 2465-2628 - www.aboutscience.eu/aboutopen

© 2024 The Authors. This article is published by AboutScience and licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0). Commercial use is not permitted and is subject to Publisher’s permissions. Full information is available at www.aboutscience.eu

The worldwide growing prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM), especially Type 2 DM, is associated with a high prescription of insulin therapy, which strongly increases the economic costs of the disease (1). Not only everyone affected by Type 1 DM but also a large proportion of those suffering from Type 2 DM, that is, the large majority of all DM subjects, often must use insulin to control hyperglycemia and to prevent/treat diabetic complications (2). This happens despite the availability of new drugs for the treatment of Type 2 DM, such as those improving the activity of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), that is, the dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors and the GLP-1 receptor agonists, and those reducing the renal glucose reabsorption by means of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors. These new compounds have greatly enlarged the family of drugs that were traditionally prescribed for the treatment of this disease, mainly sulfonylureas and metformin, adding specific advantages in terms of cardiovascular and kidney protection (2). Despite these new opportunities, a large proportion of Type 2 DM subjects still need insulin, alone or in combination with the abovementioned drugs, to control hyperglycemia and this happens especially in those with long-standing DM, because of the progressive decline of beta-cell function and endogenous insulin production that is a feature of the disease (3).

Brief history of insulin therapy

Insulin was used for the first time in the treatment of a patient with DM a hundred years ago, that is, in 1922, by the Nobel laureate Frederick Banting and his collaborator Charles Best. Until 1980, it had been extracted from bovine and then from pork pancreas, whose insulin had only one amino acid difference from the human one, and then purified until the so-called “monocomponent insulins,” which are preparations without impurities, were obtained. In 1936 the first “lente” insulin, a product whose absorption was delayed by adding a basic protein and covering the need for about 12 hours, was obtained and called NPH (Neutral Protamine Hagedorn) and it is still in use. Successively, delaying of insulin absorption/activity was also obtained by adding zinc to the extractive hormone and transforming the physical state of the drug in the vial from solution to suspension, with more prolonged activity when more zinc was added (Semilente, Lente, and Ultralente insulins) (4). The stability of compounds containing regular, that is, unmodified, and prolonged insulin, both NPH and zinc-suspended, also gave the possibility of mixing them in the same syringe, either at the moment of the injection or in premixed preparations with different rapid/prolonged insulin ratios (5).

Insulin as a biological drug

In the late 1970s human insulin was synthesized by means of recombinant deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) techniques applied to some microorganisms and it became the first biological drug ever obtained, largely available and not expensive. Soon after, with the aim of improving its pharmacological characteristics, some modifications were made to the original human molecule in order to obtain more rapid-acting products for prandial needs and more stable and prolonged drugs for basal insulinization; they were called insulin analogs. Actually, three different short-acting (Lispro, Aspart, and Glulisine), one ultrafast-acting (FiAsp), and four long-acting (Glargine U100, Detemir, Glargine U300, and Degludec) insulin analogs are available on the market, together with the recombinant human insulin (6).

The improved pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of insulin analogs, in comparison with human insulins, did not result in a better metabolic control as expressed by hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels, but it reduced the risk of the most worrying complication of insulin therapy, that is, hypoglycemia, with lower blood glucose variability, and this explains why their use has rapidly increased in all the countries where they are available. Analogs, however, are even more expensive than human insulins; in the Italian market the price of analogs is two to three times greater than that of human insulins and the same usually happens in the international market (7). The global insulin market size was valued at $18.73 billion in 2022 and is projected to grow from $18.95 billion in 2023 to $21.04 billion by 2030. It has registered a 5% decline during the pandemic year 2020, with a subsequent sharp increase in the following years 2021 and 2022 (7). Almost three-fourths of this market is represented by insulin analogs (8).

Taken together, both the increasing number of subjects treated with insulin and the growing prices of the drug explain what, especially in Western countries, has been claimed as the “Insulin Crisis,” that is, a progressive and poorly sustainable escalation of the costs that national health systems pay for insulin or, in the case of private insurance companies as in the United States, a reduced coverage for this expenditure. In this latter case many patients autonomously reduce the daily insulin dose to save money, with catastrophic consequences in terms of quality and outcomes of diabetes care (7).

Biosimilars

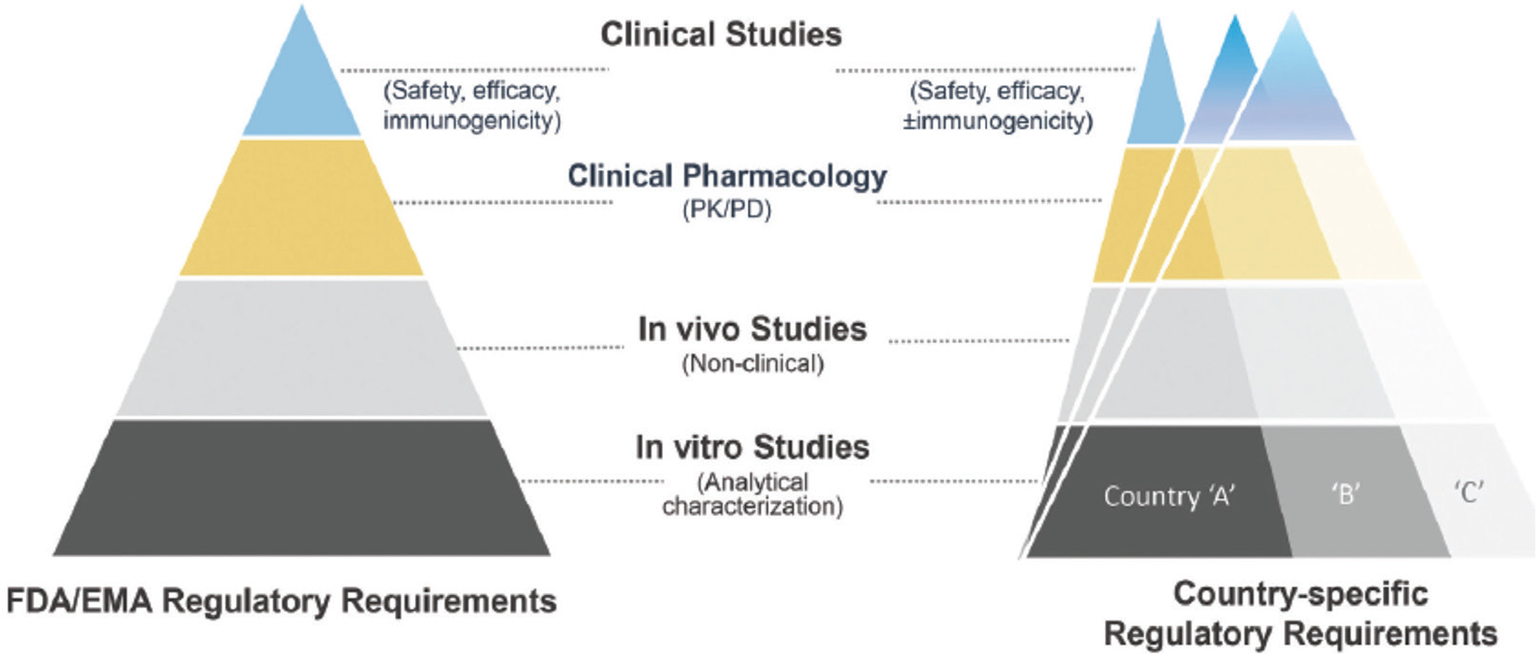

In the field of chemical drugs a valid cost-saving instrument has been the substitution of the branded products with the so-called “generic” ones, when the patent of the originator drug expires. The same can also be done in the field of biological drugs, as insulin analogs are, obtaining what are known as “biosimilars” (9). There are, however, some important differences between generic drugs, which usually are small chemical molecules with standard and predictable efficacy, and biosimilars, whose structure is much more complex and whose production is much more expensive. Since biosimilars are designed to match the structure, function, and clinical effects of an already licensed reference biological product, a head-to-head comparison with the reference/originator biologic drug and other quality attributes is required to demonstrate the biosimilarity of the proposed drug. Also, once demonstrated, the comparable analytical characterization and similarity of the biosimilar with originator needs to be followed by clinical evaluation and this requires specific clinical trials (10) (Fig. 1). Consequently, the biosimilar price is not so lower than that of the originator as it happens with the generic drugs; however, an approximately 25%-30% cost saving is common. If applied to the global insulin market, this could theoretically lead to about a $4 billion saving.

Fig. 1 - Biosimilar development steps (from Joshia et al (10)).

Glargine U100 was the first insulin analog that lost its patent protection in 2015, followed in recent years by the rapid-acting analogs Lispro and Aspart; for all these insulins biosimilars are today available in the international market. Despite this, and despite the evidence of similar efficacy and safety with analogs (11), the biosimilar insulin market does not grow as it happened with the generic drugs or with other biosimilars. In England it has been estimated that from 2015 to 2018 the use of Glargine biosimilar generated only a minimal part (3.42%) of the potential savings (12).

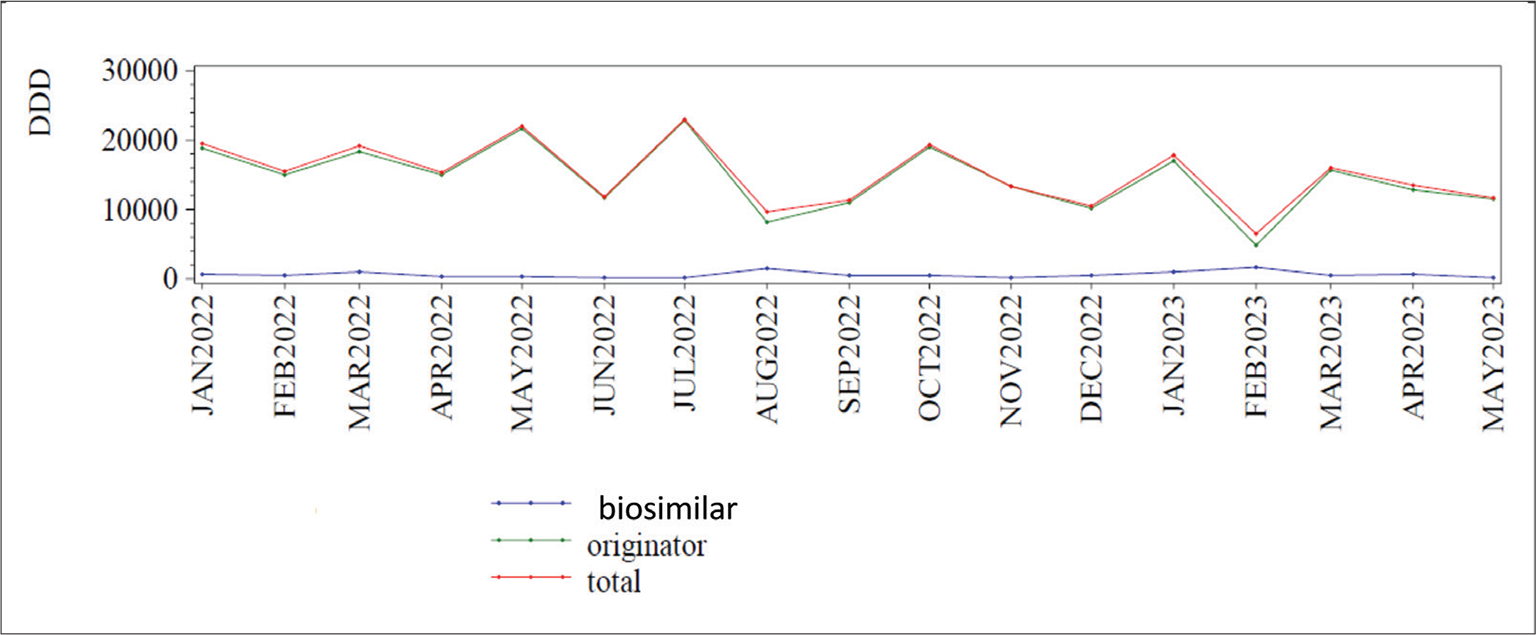

In Italy biosimilars account for <20% of the total expenditure for insulins and there is no evidence of increase: from January 2022 to May 2023 this percentage has been substantially stable (13) (Fig. 2). In a large international survey concerning the utilization of long-acting insulin analogs and their biosimilar in some Asian countries, it has been shown that there is an increasing use of long-acting insulin analogs across all countries, while that of long-acting biosimilar insulins is very different: it is high in countries such as Bangladesh, India, and Malaysia where they are produced, but it is low in other regions (Japan, Korea), perhaps because of the reduced price gain and the lack of local promotional activities. Accordingly, they suggest that implementation of these activities, both local production and stakeholder awareness, can help increase their use and the related beneficial effects (14).

Fig. 2 - Global Italian market of biosimilar and originator insulins from January 2022 to May 2023. DDD = daily defined dose. From Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (13)).

Biosimilars and the “insulin crisis”

As a general rule, biosimilars are more expensive than generic drugs, because of the complexity of their molecules, the need for specific and highly qualified manufacturing skills, and even the small differences with the originator that require new clinical trials and revisions from local regulatory authorities, in order to assess that efficacy and safety are preserved. Consequently, their costs are not very different from that of the originators and the economic gain coming from their use is reduced, especially if compared with that of generic drugs. This doesn’t, however, explain why in most countries utilization of other biosimilars, as those used in rheumatology, hematology, and oncology, is growing and it is much greater than that of the originators: local health policy rules concerning prescription and reimbursement can play a role, similar to attitudes and barriers in physicians and in patients who can be misinformed about safety and efficacy of biosimilar insulins (15).

It is evident that biosimilars can be a useful instrument to overcome the “insulin crisis” and to reduce the global expenditure for diabetes care all over the world (16). This means that their use must be encouraged with initiatives from health care authorities such as those allowing a reduction of their costs, a preferential channel for prescription/reimbursement in comparison with originators, and incentives to their production and utilization. On the side of physicians and patients, a better information about efficacy and safety is clearly warranted. Putting together these and other indications, biosimilar insulin use will certainly grow and it will became a safe and effective way to reduce costs while preserving quality and efficacy of diabetes care, which perhaps is the best instrument against the “insulin crisis.”

Disclosure

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding/support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1. Bommer C, Sagalova V, Heesemann E, et al. Global economic burden of diabetes in adults: projections from 2015 to 2030. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(5):963-970. CrossRef PubMed

- 2. Davies MJ, Aroda VR, Collins BS, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2022. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia. 2022;65(12):1925-1966. CrossRef PubMed

- 3. Russo GT, Giorda CB, Cercone S, De Cosmo S, Nicolucci A, Cucinotta D; BetaDecline Study Group. Beta cell stress in a 4-year follow-up of patients with type 2 diabetes: a longitudinal analysis of the BetaDecline Study. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2018;34(6):e3016. CrossRef PubMed

- 4. Home PD, Mehta R. Insulin therapy development beyond 100 years. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9(10):695-707. CrossRef PubMed

- 5. Cucinotta D, Russo GT. Biphasic insulin Aspart in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10(17):2905-2911. CrossRef PubMed

- 6. Kramer CK, Retnakaran R, Zinman B. Insulin and insulin analogs as antidiabetic therapy: a perspective from clinical trials. Cell Metab. 2021;33(4):740-747. CrossRef PubMed

- 7. Fralick M, Kesselheim AS. The US insulin crisis. Rationing a life-saving medication discovered in the 1920s. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(19):1793-1795. CrossRef PubMed

- 8. Fortune Business Insights. Pharmaceutical. Human Insulin Market Size. May 2023 Online. Accessed November 2023.

- 9. Liu Y, Yang M, Garg V, Wu EQ, Wang J, Skup M. Economic impact of switching from originator biologics to biosimilars: a systematic literature review. Adv Ther. 2019;36(8):1851-1877. CrossRef PubMed

- 10. Joshia SR, Mittra SB, Rajb P, Suvarnab VR, Athalyeb SN. Biosimilars and interchangeable biosimilars: facts every prescriber, payor, and patient should know. Insulins perspective. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2023;23(8):693-704. CrossRef

- 11. Yang LJ, Wu TW, Tang CH, Peng TR. Efficacy and immunogenicity of insulin biosimilar compared to their reference products: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Endocr Disord. 2022;22(1):35. CrossRef PubMed

- 12. Agirrezabal I, Sánchez-Iriso E, Mandar K, Cabasés JM. Real-world budget impact of the adoption of insulin glargine biosimilars in primary care in England (2015–2018). Diabetes Care. 2020;43(8):1767-1773. CrossRef PubMed

- 13. Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (AIFA). National report on medicines use in Italy. 2022. OnlineAccessed November 2023.

- 14. Godman B, Haque M, Kumar S, et al. Current utilization patterns for long-acting insulin analogues including biosimilars among selected Asian countries and the implications for the future. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(9):1529-1545. CrossRef PubMed

- 15. Aladul MI, Fitzpatrick RW, Chapman SR. Healthcare professionals’ perceptions and perspectives on biosimilar medicines and the barriers and facilitators to their prescribing in UK: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(11):e023603. CrossRef PubMed

- 16. Socal MP, Greene JA. Interchangeable insulins. New pathways for safe, effective, affordable diabetes therapy. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(11):981-983. CrossRef PubMed